Readers of The Ravenstones will doubtless claim that I owe a great deal to C.S. Lewis and the Narnia series.

Rightfully so, and I’d be the first to admit it. I’m a great fan of Lewis, and not just for The Chronicles of Narnia, but also his brilliant, insightful religious works (The Screwtape Letters, The Pilgrim’s Regress, etc.) and science fiction trilogy (Out of the Silent Planet, Perelandra and That Hideous Strength. (At one time I considered writing under a pen name based on its hero, Elwin Ransom.)

Pan Books, London, 1983

I’m sure I owe just as much to other authors, including J.R.R. Tolkien, Lewis Carroll and Kenneth Grahame. We all stand on the backs of those who came before us, no matter what profession. For most of us literary newcomers, all we can really hope for is to give old tropes and sagas a new twist, a surprise or two and some engaging characters.

I’ve quoted Bruce Handy before (see here and here). In his book Wild Things: The Joy of Reading Children’s Literature as an Adult he devotes a chapter to Lewis (‘God and Man in Narnia’). It’s well worth reading (as are all the other chapters). Handy starts off by paying homage to the first line of The Voyage of the Dawn Treader:

“There was a boy called Eustace Clarence Scrubb, and he almost deserved it.”

By any measure, that’s a terrific first line. As Handy notes, it’s funny, it reveals both the craftsmanship of the author and the character in question and it demonstrates generosity (although he “almost deserved it”, Master Scrubb can still be saved from such a terrible fate). (pp. 161-2)

This observation led me to look at the first lines of all seven books in the Narnia series. In my view, the only other opener that comes close to the perfection of this line is the one from The Silver Chair:

“It was a dull autumn day and Jill Pole was crying behind the gym.”

Although not quite as good, the reader immediately understands the time and place and will want to know why she’s crying.

While Handy does not believe in God, he still found himself “charmed and persuaded by the religious undercurrents of Lewis’s tales” and is moved by the author’s ability to “convey in tangible, organic terms what his religion means to him, what Christianity feels like for him.” (p. 174)

Aslan, of course, is the centrepiece of the story – the description of the lion, his humiliation, death and resurrection is awe-inspiring, moving and full of majesty, as one would expect in coming face to face with the incarnation of God. When Handy describes the children’s mourning over Aslan’s death as blending “beauty, empathy, and sorrow with formality and even stiffness” (p. 166) I’d say he has captured that combination of emotions exactly.

It seems that Lewis was hesitant to push his allegory on his many readers. According to George Sayer, Lewis’s friend and biographer, apart from a desire to write “good stories”, his “idea … was to make it easier for children to accept Christianity when they met it later in life. He hoped that they would be vaguely reminded of the somewhat similar stories that they had read and enjoyed years before.”

It was my mother who first introduced me to Narnia and Lewis, although she never proselytised the religious aspects of his work. We had a boxed set of the seven volumes in paperback, which ended up with my sister. I replaced that set with another (a 50th anniversary set using the original illustrations) much later in life.

According to Handy, the Narnia story began not with a plan to tell a digestible child-friendly version of Christianity but with a series of images – a faun carrying parcels through a snowy forest, a witch riding a sleigh, etc.). He goes on to discuss Lewis’s imagination, the delightful scene where Lucy first makes her way through the wardrobe, the humor in Lewis’s writing, the premature death of his mother (a fate that also overshadowed Tolkien, although in Tolkien’s circumstance, his mother was also ostracized by the family for her conversion to Catholicism), Tolkien’s criticisms of the series inconsistencies and much, much more. As there’s too much to detail here, I’d encourage interested readers to check out Handy’s book for themselves. It’s well worth the read.

Let me finish this post with praise for Narnia’s original illustrator, Pauline Baynes. As my readers know, I consider illustrations to be a crucial component of any book. A picture is worth a thousand words, as they say. Thus, the choice of the illustrator (especially the cover artist) can make or break it.

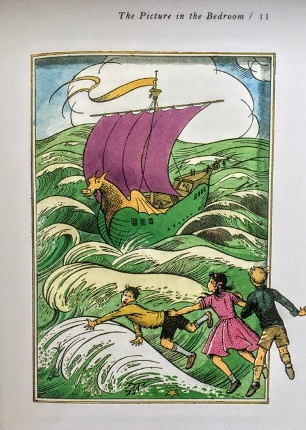

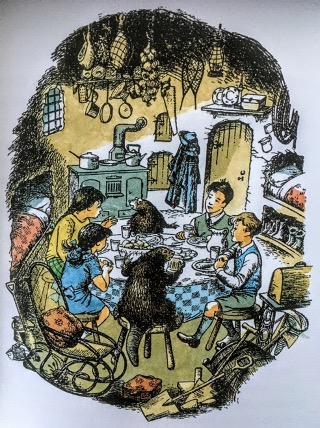

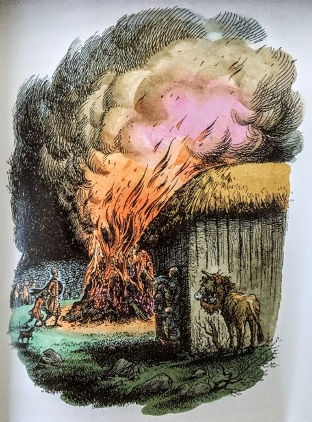

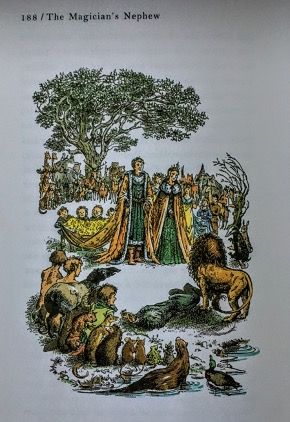

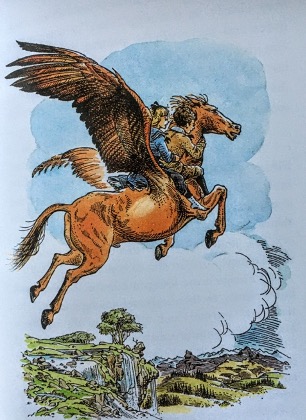

Baynes was introduced to Lewis by Tolkien, for whom she’d produced illustrations for several of his earlier works. She was, in fact, much closer to Tolkien and her relationship with Lewis, it seems, remained ambivalent, at best. Here are a few examples from the Narnia tales:

Baynes’s bibliography is impressive and extensive (check out her Wikipedia listing). I like the lightness of her artwork in the Narnia books: they capture the essence of Lewis’s story and message – the coziness of the habitats, the essential character of the many creatures and the drama of key events (see samples above and below).

That praise being noted, I don’t think the illustrations work well as covers (unfortunately they were employed as such for the series I own). Here, they’re too busy and blurry for my liking. (I much prefer the simplicity and art deco aspects of Chris Van Allsburg’s drawings for the 1994 HarperCollins edition.)

Cover of The Dawn Treader drawn by Chris Van Allsburg, HarperCollins, 1994 Edition of The Chronicles of Narnia

You must be logged in to post a comment.