This post comes out on November 11, Remembrance Day in Canada (and other parts of the Commonwealth) and Veterans’ Day in America; as such, like last year, it reflects on the matters of war and peace, and recognizes the sacrifice of so many service men and women who gave so much in the name of democracy and justice.

At first blush, it’s hard to comprehend H. G. Wells, the prolific author of many amazing books of science fiction (The War of the Worlds and The Time Machine, most notably) and noted advocate for world peace and social equality, having once written a set of rules for playing war games, even if his focus was on toy soldiers.

Timing in life is everything, of course, even in the world of book publishing. Little Wars was published in 1913, a full century since the last great world conflict (the Napoleonic Wars) and 40 years (more than a generation) after the last minor European war, at a brief moment when the European public had forgotten the devastation and torment that accompanies glorious cavalry charges and heroic sacrifices. But just a year later, the First World War began, when “man’s innocence vanished for ever” (as Issac Asimov writes in his Foreword to the 1970 reissue), “the glamor of war vanished and ‘Little Wars’ went out of fashion…”

The full title of the book is Little Wars (A Game for Boys from twelve years of age to one hundred and fifty and for that more intelligent sort of girl who likes boys’ games and books). I’m sure readers will agree the title is unlikely to be an acceptable or winning one these days. Although it went out of print for many years, a “facsimile reproduction of the first edition” was published by Arms and Armour Press (a division of Macmillan) in 1970. That was the edition that I purchased (online) several years ago.

The idea for a set of rules for war games came about not long after the British toy maker, William Britain, revolutionized the production of toy soldiers (1893). By devising a method of hollow casting, the company was able to make soldiers of lead, rather than the tin used by their German originators (and competitors). The resulting toys, cheaper and lighter than their counterparts, became generally available to the rising middle class of consumers. I suspect jingoism and imperialism also had something to do with their popularity, but that would be the subject of a much larger paper.

Most boys of my generation owned lead-cast soldiers (usually the ubiquitous British Coldstream Guards), with which war games were played. Invariably, the rifles and heads broke off after a time; still, one kept playing with them, that is until they became unrecognizable. Eventually (late 1960’s) lead was replaced by the safer, more durable (and cheaper) plastic. Although W. Britain still makes and sells toy soldiers (as collectibles) the company is now owned by an American firm called First Gear. Toronto’s Royal Ontario Museum holds a fantastic sampling of Britains Ltd’s collection of toy soldiers (my photographs):

Coldstream Guards, Royal Ontario Museum

French Foreign Legion, Royal Ontario Museum

Coldstream Guards Band, Royal Ontario Museum

But, as usual, finding my subject so compelling, I’ve begun to digress onto tangents. Let’s return to the book.

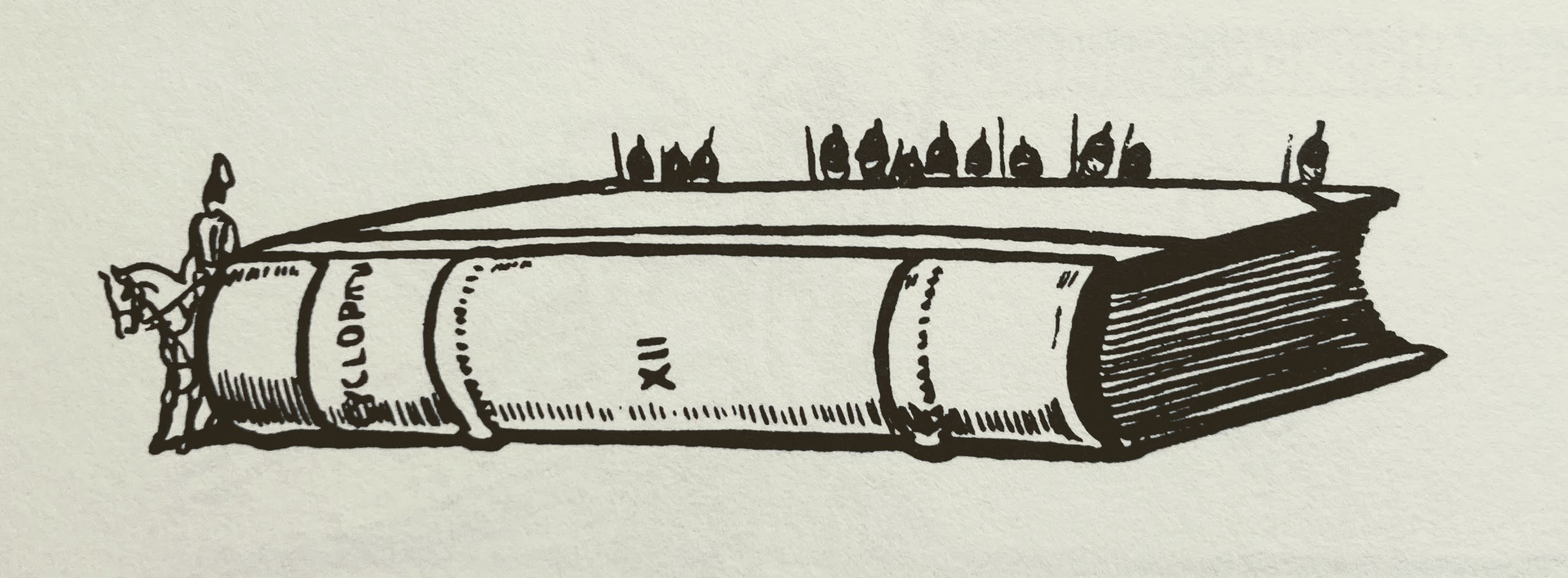

In Little Wars, Wells explains the origins of the idea for such a book, giving credit to the invention of a toy spring breech-loaded cannon capable of hitting a toy soldier “nine times out of ten at a distance of nine yards” (p.9) and to the noted humorist Jerome K. Jerome (Three Men in a Boat, 1889) with whom he was playing the game of war. The rules evolved over time, with the addition of obstacles and a landscape (“volumes of the British Encyclopedia and so forth, to make a country”, p.13) and time limits. Eventually, separate rules for infantry, cavalry and artillery were created.

Although the conduct of war is a serious matter and I don’t wish to trivialize the subject, especially these days, the book is written in a playful, tongue-in-cheek manner, Chapter IV, The Battle of Hook’s Farm, in particular. Here, Wells becomes General H.G.W. of the Blue Army, providing a blow-by-blow account of the encounter, with battlefield photographs by a “daring woman war correspondent, A.C.W.” (the initials of Wells’ second wife, Amy Catherine). The ink-stained author is transformed into a manly field commander, replete with extravagant moustache and battle scar over one eye. In the end, the Blue Army prevails and the Red Army retreats from the field of play.

Photographs by the author of the table-top layouts and drawings by J.R. Sinclair (who illustrated a 1910 version of Alice In Wonderland) add to the book’s appeal.

Finally, lest anyone think that the pacifist Wells had taken leave of his senses and become a war-monger, the author concludes Little Wars by saying (pp. 97-100):

“How much better is this amiable miniature than the Real Thing! Here is the homeopathic remedy for the imaginative strategist…No smashed nor sanguinary bodies, no shattered fine buildings nor devastated country sides, no petty cruelties, none of that awful universal boredom and embitterment, that tiresome delay or stoppage or embarrassment of every gracious, bold, sweet, and charming thing, that we who are old enough to remember a real modern war know to be the reality of belligerence.

“This world is for ample living; we want security and freedom; all of us in every country…We want fine things made for mankind – splendid cities, open ways, more knowledge and power, and more and more and more, and so I offer my game…and let us put this prancing monarch and that silly scaremonger, and these excitable ‘patriots’ and those adventurers… into one vast Temple of War with cork carpets everywhere, and plenty of little trees and little houses to knock down, and cities and fortresses and unlimited soldiers…and let them lead their own lives there away from us.

“My game is just as good as their game and saner by reason of its size. Here is War, done down to rational proportions and yet out of the way of mankind.

“I would conclude…with one other disconcerting and exasperating sentence for the admirers and practitioners of Big War. I have never met in little battle any military gentlemen, any captain major, colonel, general, or any eminent commander who did not get into difficulties and confusions among even the elementary because of the Battle. You have only to play at Little Wars three or four times to realise just what a blundering thing Great War must be.

“Great War is at present, I am convinced, not only the most expensive game in the universe but it is a game out of all proportions. Not only are the masses of men and material and suffering and inconvenience too monstrously big for reason, but – the available heads we have for it, are too small. That, I think, is the most pacific realisation conceivable, and Little War brings you to it as nothing else but Great War can do.”

Cover Photo by Ian Taylor on Unsplash

You must be logged in to post a comment.