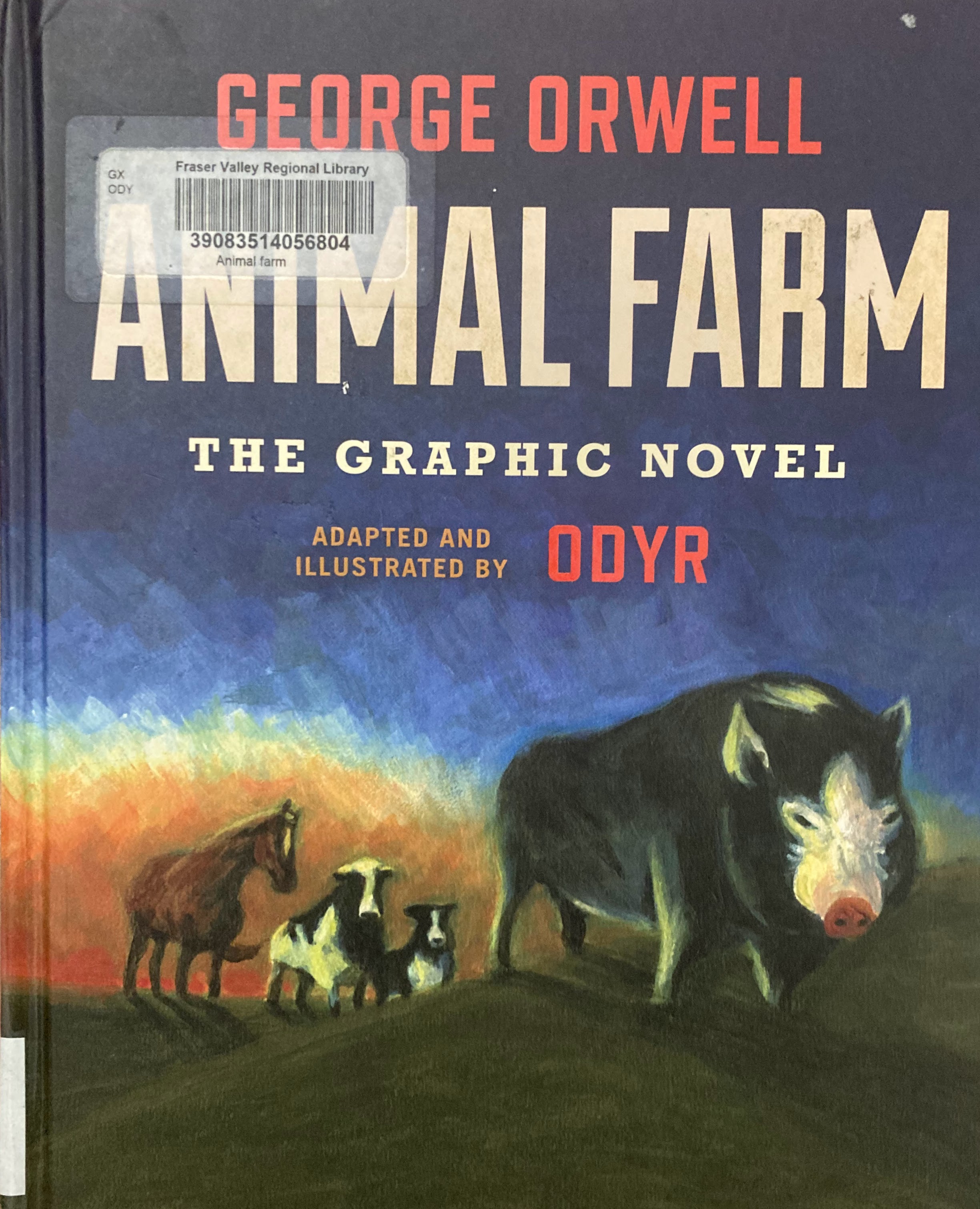

A month ago I wrote about the challenge of turning The Ravenstones into a graphic novel and, in the process of researching what was involved, that I’d come across an illustrated version of Animal Farm in my local library (first published in Portuguese as A Revoluçâo dos bichos in Brazil in 2018; this English version by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019):

I had not read George Orwell’s book in decades and had forgotten its tremendous impact. Of course, for someone who writes about anthropomorphic creatures, the novel has special resonance: it may be the ultimate anthropomorphic tale. I can still recall identifying with one of the farm animals upon my first reading of this powerful political satire.

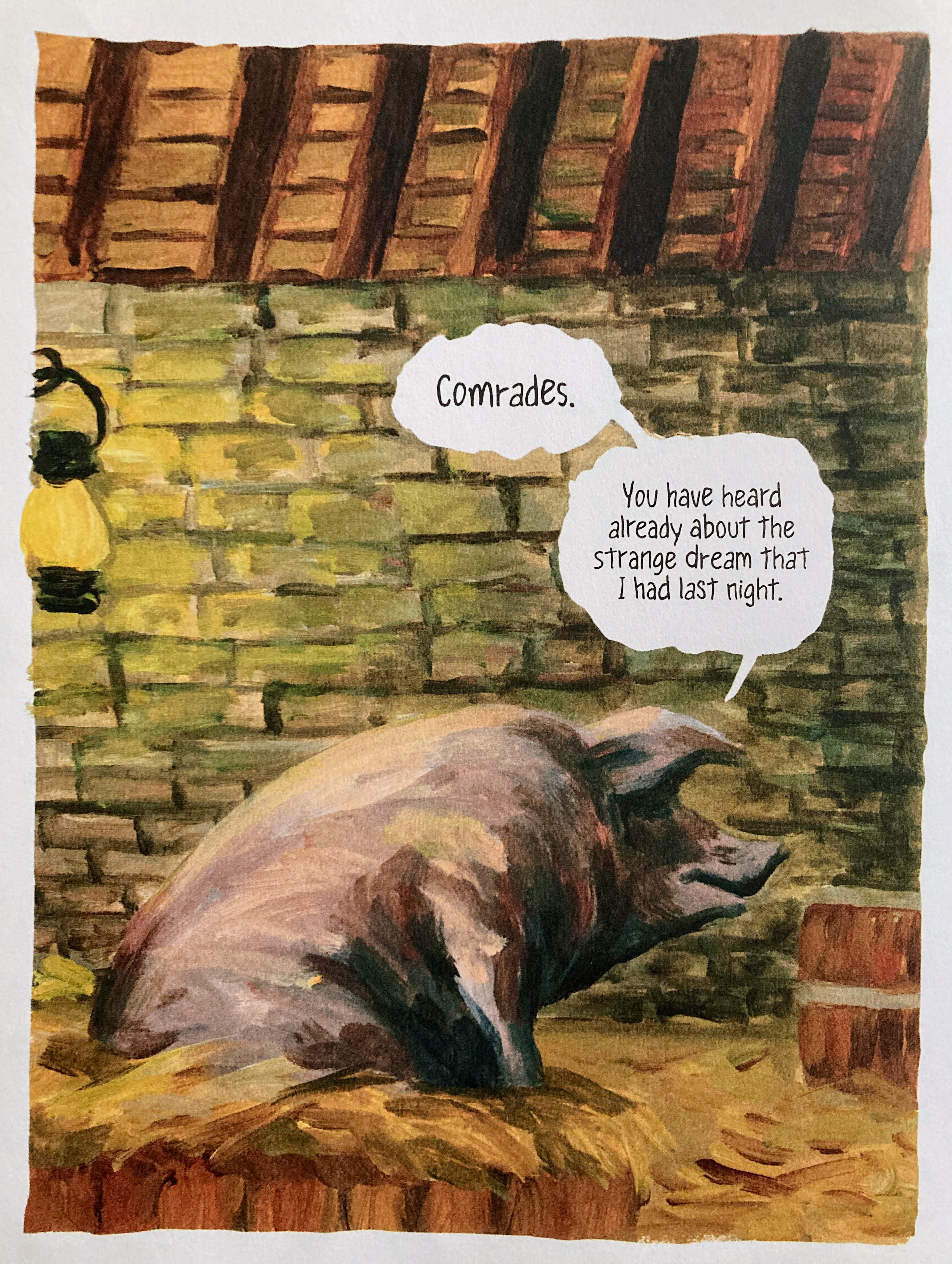

Animal Farm serves as an allegory for the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the subsequent development of the Soviet Union. Inspired by the dreams of an aged pig named Old Major, a group of farm animals rebel against their human farmer, Mr. Jones, in the hope of bringing an end to their oppression establishing a fair and equal society.

They succeed in taking over the farm and renaming it “Animal Farm,” with a set of principles known as the Seven Commandments guiding their new society:

- Whatever goes upon two legs is an enemy.

- Whatever goes upon four legs, or has wings, is a friend.

- No animal shall wear clothes.

- No animal shall sleep in a bed.

- No animal shall drink alcohol.

- No animal shall kill any other animal.

- All animals are equal.

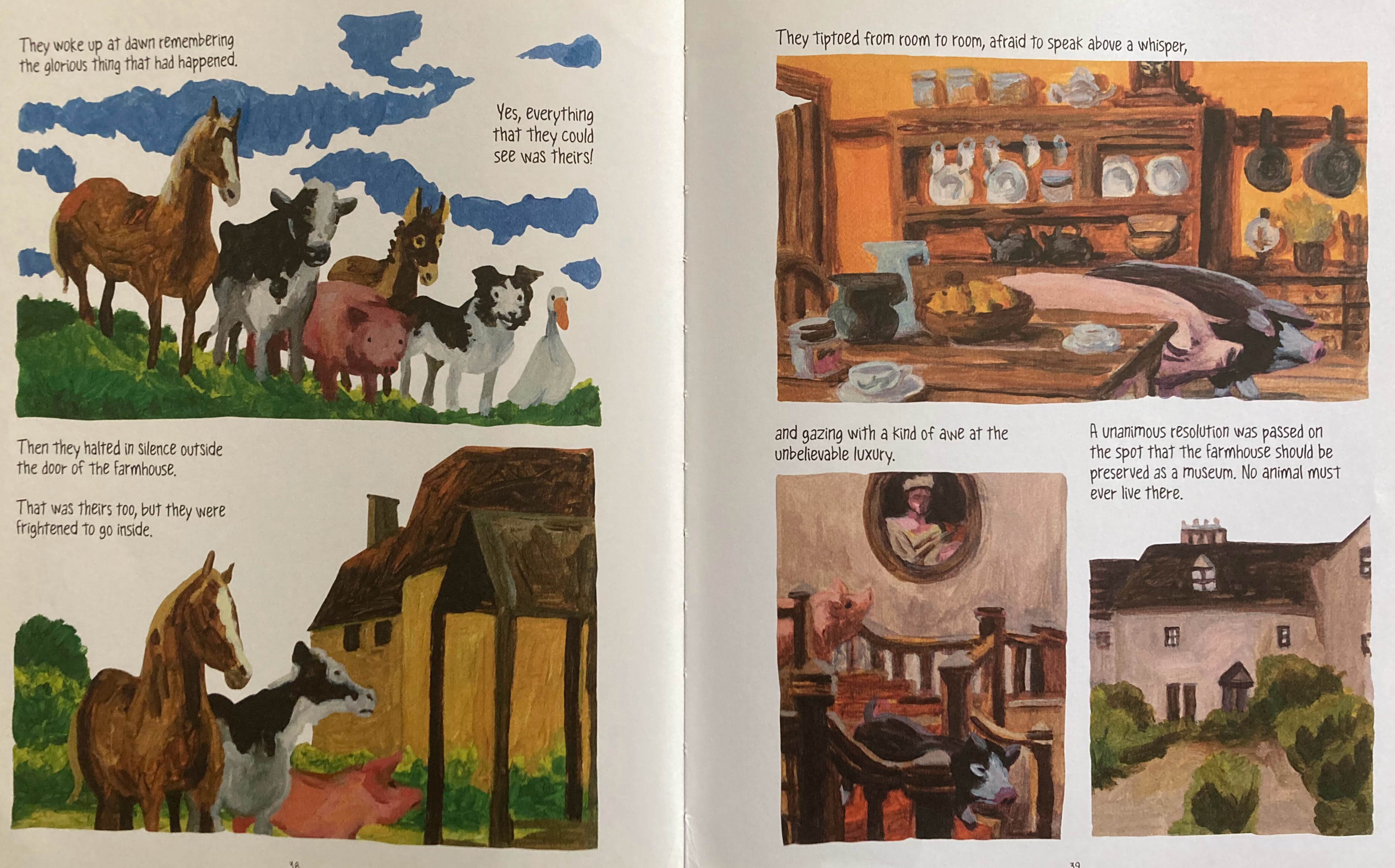

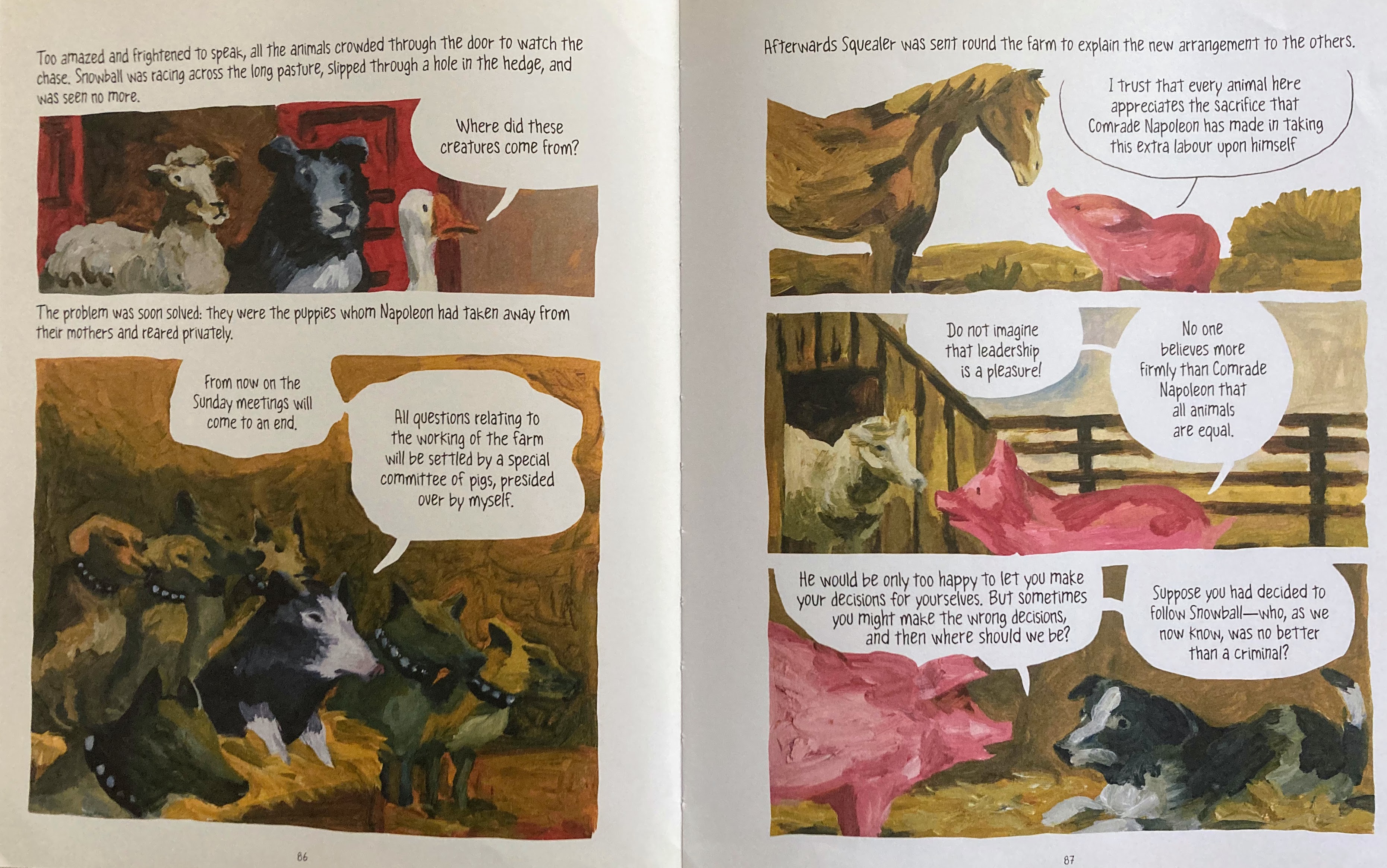

Initially, the animals experience a sense of freedom and equality. But over time, the pigs, led by Napoleon (i.e. Stalin) and Snowball (i.e. Trotsky), seize power and become corrupt, betraying the principles they had initially set. The Seven Commandments are gradually altered to justify the pigs’ actions, and they begin to resemble the oppressive humans they once despised.

As the pigs take more control, they modify the commandments to serve their own interests, eventually leading to the famous alteration of the seventh commandment to: “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.” This one change epitomizes the hypocrisy and inequality that develop within the leadership of Animal Farm, highlighting the betrayal of the original lofty ideals.

Much of what occurs in the novel – the dream of Old Major (Karl Marx), the battles against the farmers, the pigs’ rise to a preeminent position in the animals’ society (the Stalinist bureaucracy), the overthrow of Snowball, the recruitment and training of the puppies (the KGB), Squealer’s efforts to justify every betrayal (epitomizing Pravda but really the propaganda machine of every dictatorship), the animals’ confession of non-existent crimes (Stalin’s purges) and so on – can be viewed as allegories for events that took place in Russia from the 1917 revolution to the time of Orwell’s writing (November 1943 to February 1944, in the latter half of World War 2).

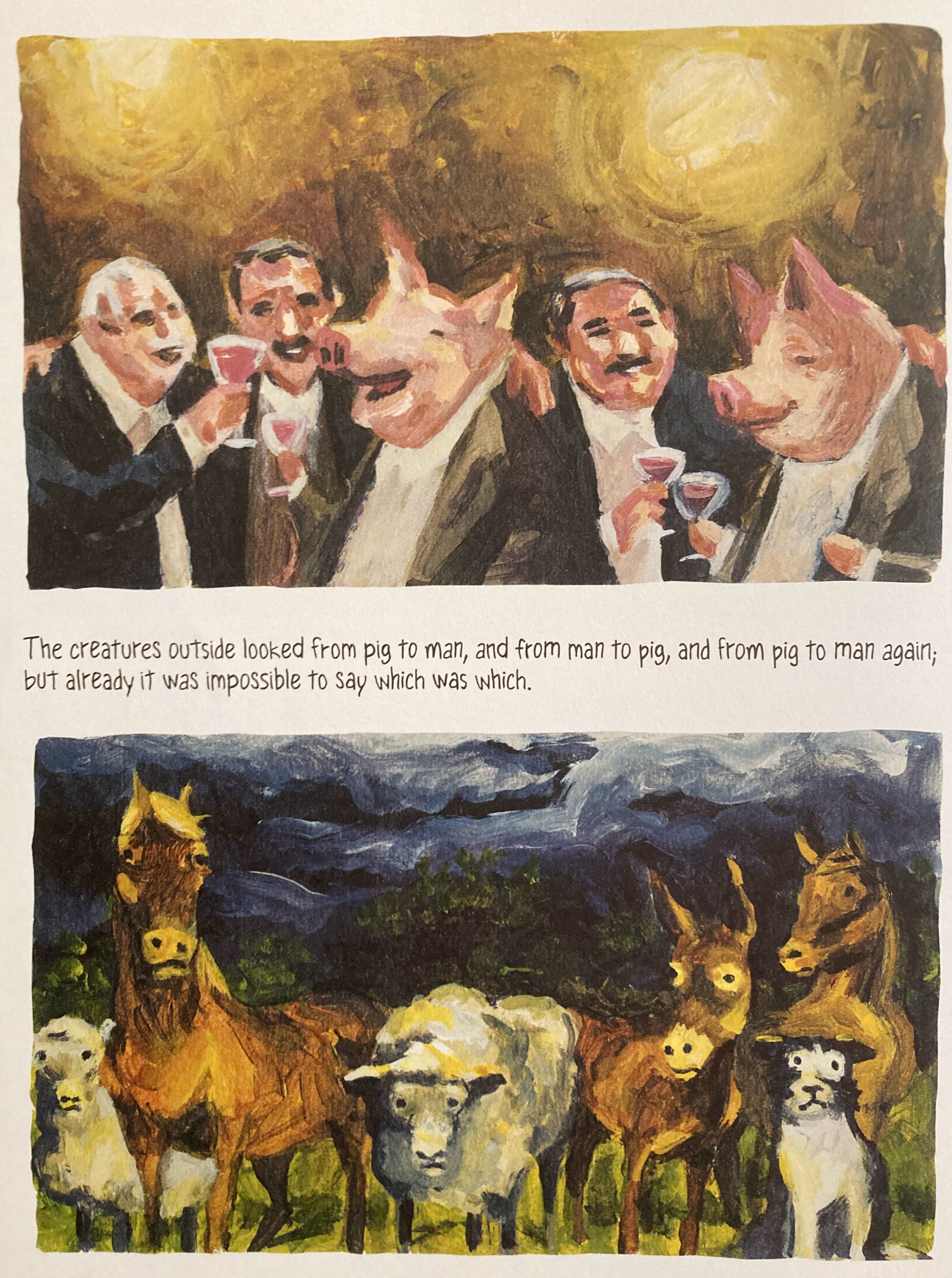

Ultimately, every commandment is broken and, in the book’s close, the rest of the farm animals can be seen standing outside looking on the pig hierarchy carousing inside with other human farm owners. “The creatures outside looked from pig to man and from man to pig, and from pig to man again; but already it was impossible to say which was which.”

Orwell found it a challenge to get the book published given the pro-Soviet sentiment of the times (the wartime alliance with the Soviet Union against Nazi Germany); four British publishers refused to accept it, one after consulting with the Ministry of Information; even Soviet spies within the British Government had a hand in its rejection by potential publishers.

Finally published in 1945 by Secker and Warburg, it slowly won favor with reviewers and the general public. Today, it is recognized as one of the last century’s greatest books. Time magazine chose Animal Farm as one of the 100 best English-language novels (from the magazine’s inception in 1923 to 2005). In 1998, it was included as number 31 on the Modern Library List of Best 20th Century Novels. In 1996, it won a Retrospective Hugo Award, the annual literary award for best science fiction or fantasy books of the year). It is now included in the Encyclopedia Britannica’s Great Books of the Western World selection (#62 in Volume 60).

Orwell was influenced by his own experiences during the Spanish Civil War (see Homage to Catalonia) and came to see that fiction was the best way for him to attack the evils of totalitarianism. The novel, a critique of dictatorship, propaganda, and the corruption of power, highlights the idea that revolutions often lead to a new form of tyranny and the dangers of not questioning authority. Far from being a fantasy story, Animal Farm is a history of events and dire warning – a devastating commentary on the nature of political systems and the human capacity for manipulation and betrayal.

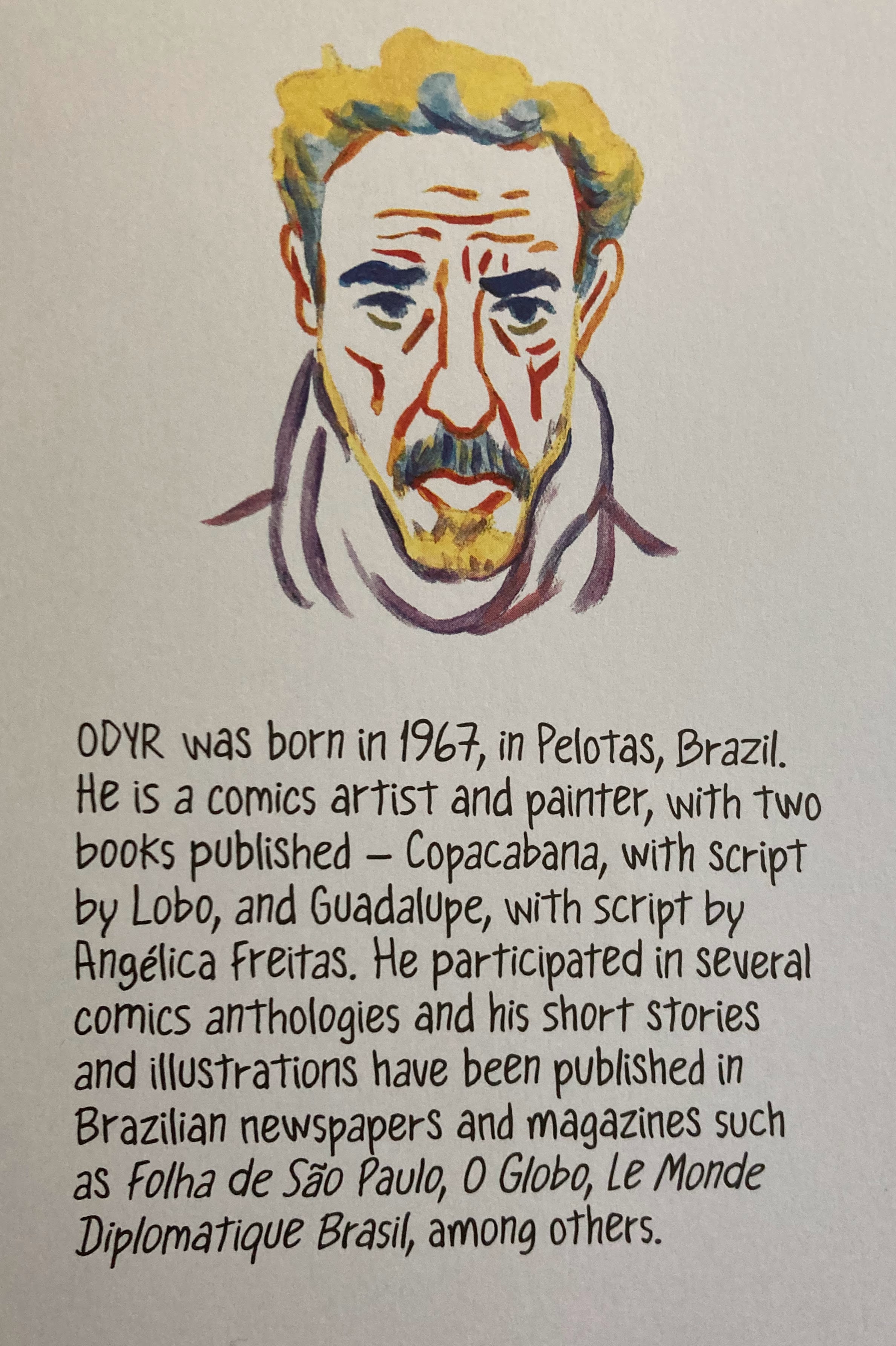

Finally, a word about Odyr Fernando Bernardi, the Brazilian illustrator. The artist was unknown to me before finding this book, and as he does not appear to have a website or Wikipedia listing in English (perhaps he does in Portuguese) I found little about his background. That being said, he has a comprehensive instagram site that’s well worth checking out and, from the back of the book, the following provides a short bio:

In researching for this post, I discovered that this edition of Animal Farm is the first ever graphic novel version of Orwell’s tale. I wish I’d the space to include more of the fine drawings, of which The New York Times declared upon publication: “This brightly coloured homage to Orwell’s timely allegory is heartbreaking and elegant. Odyr’s images of animals casting off their bonds and then living with the results of their revolution are painterly and evocative, both loose and illuminating.”

I couldn’t agree more.

You must be logged in to post a comment.