Last weekend I read that Flaco, the Eurasian eagle-owl had died. About a year ago, vandals had let the bird free from New York’s Central Park Zoo, after which he’d enjoyed a life on the lamb, much to the amusement and/or concern of the public and media. On Feb. 23, the “Wildlife Conservation Society, which operates the zoo, said in a statement that Flaco had been found on the ground after hitting a building on West 89th Street.”

The Eurasian eagle-owl, as its name would suggest, is one of the largest breed of owls, sporting a wing span of up to six feet. These birds can live up to 20 years in the wild, but up to 40 in captivity. Poor Flaco was only 13. The New York Times (NYT) story of his death has, as of this writing (a week ago), has generated over a 1100 comments. Here’s one such comment:

“Having had several opportunities to marvel at and photograph this beautiful creature, I’m as deeply upset by this news as we all are. Flaco had become something of a mascot for NYC and brought out the appreciation and love for nature that’s in almost all of us. On the flip side, I’m concerned by the common projections onto this bird of human concepts and emotions. In the minds of some, his enclosure morphed into “incarceration” while the act of vandalism that separated him from his home was transmogrified into “liberation”. The end result of our year-long “reality show” binge over Flaco is that he’s now dead. Some would claim that a year’s worth of “freedom” is worth more than 20 in an enclosure at the zoo. Maybe. Or maybe not.”

Living out in British Columbia, near to nature, I can easily relate to these observations. Twice last summer and once in late fall, my home in the southwestern coastal region of British Columbia was visited by a Great Horned Owl.

Although I did not see the bird, not only did I hear it, I was also able to identify its distinctive “hoo-WHOO-hoo-hoo-oo” thanks to my Cornell Lab Merlin sound recording app. Even better, on the third occasion, two owls showed up, calling back and forth to each other. Now, that was a real treat.

Owls don’t usually show up at convenient hours. The first one started calling at 4:19 am on July 30 (at least that’s when it woke me up); the second on September 3 at 5:44 am. Of course it could have been two different owls or the exact same bird coming back for a second visit.

Even if I’d caught sight of it in the neighbouring forest, I doubt that I’d be able to tell the difference. In either case, the owl didn’t stay long; heading off after about 20 minutes to scout out new territory. The third visit from the duo also came at 5:40 am, so at least some consistency in timing exists. And they, too, disappeared after a very short time.

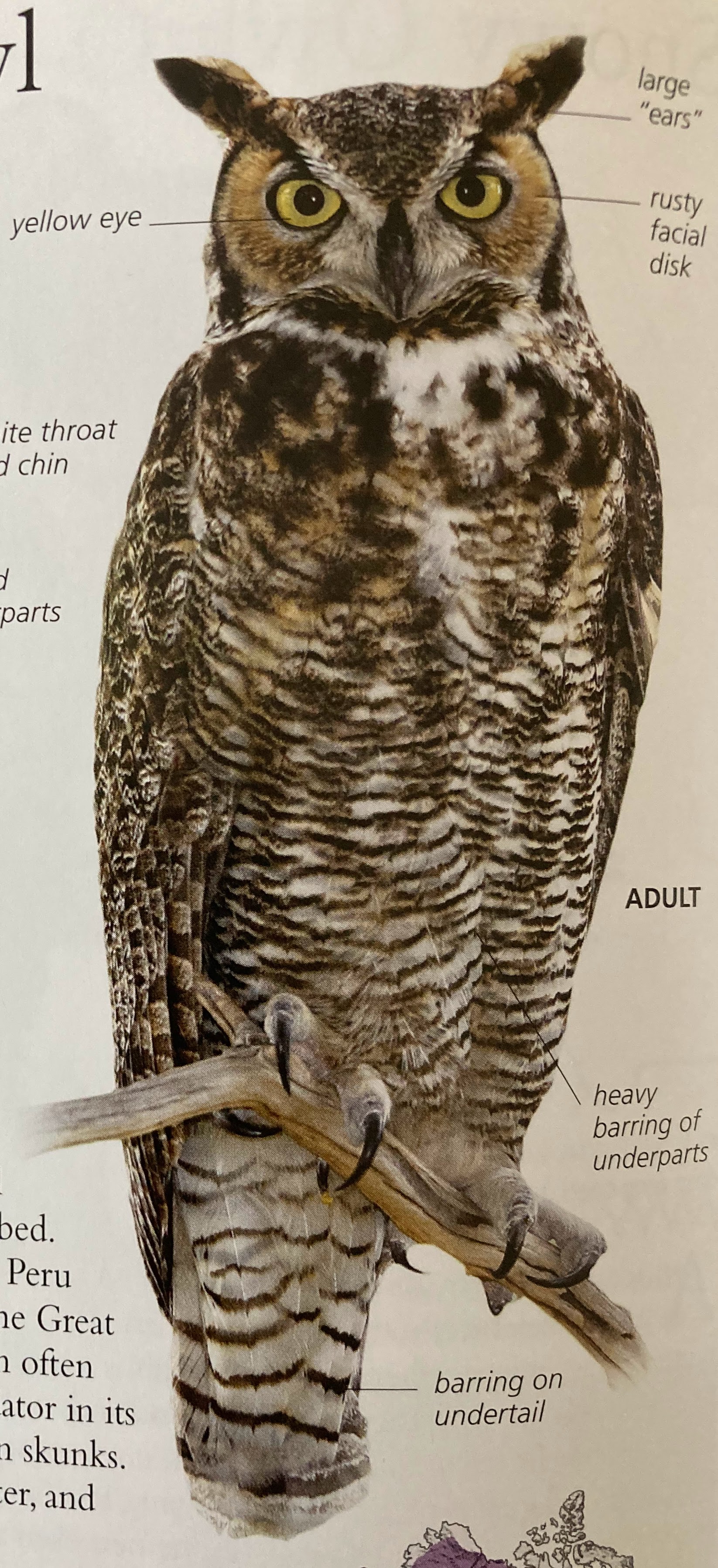

Photograph taken from my copy of Birds of North America (Dorling Kindersley, London, 2009), p. 336

A “cool fact” about the Great Horned Owl, according to the Cornell Lab: when clenched, its strong talons require a force of 28 pounds to open. The deadly grip, I read, is used to sever the spine of large prey.

Having spent much of the past decade writing my Ravenstones’ series and thinking about several types of birds and one owl in particular, I can relate to every comment about poor Flaco. I’ll leave you with two typical remarks, both widely recommended and shared by NYT readers:

“I had the good fortune to hear Falco Thursday night. He was somewhere on 86th between CPW and Columbus. I know it’s ridiculous but he sounded lonely to me. I could relate ~~ it’s a big city to be out and about on your own. Rest in peace.”

“This makes me so sad. We visited New York in October for my birthday and happened to be strolling through Central Park when we noticed a crowd of people looking up at “something” in a tall tree. A kind New Yorker informed us that it was Flaco and proceeded to tell us his story and showed us some incredible photos she had taken of him over several months. He was truly majestic and beautiful and he died free. Fly on, Flaco.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.