The original title for this post was: “A Popular History of Philosophy”. My second choice had been: “Whatever happened to Maurice Kaunitz?”

However, doubting either subject heading would entice anyone to read what came next, and imagining no one would ever bother opening the resulting post, I figured I’d better change it.

I hope you’ll forgive me for this sleight of hand. It is, in any event, the point of this essay.

Now don’t get me wrong. The subject of philosophy has always interested me. I’d taken a few introductory courses at university (ethics; political philosophy) and, not long ago, I quite enjoyed reading through one of my son’s university textbooks on the subject:

And here is the book which generated this post – the latest addition to my library and one that has proven to be of real quality.

And since it was a Christmas gift from my granddaughter, buying it at a nearby Vancouver store specializing in nostalgia and vintage curiosities, it will always hold a special place in my heart.

Not just that, the book holds a mystery. And that mystery is its author.

It is written by one Maurice M. Kaunitz. Have you ever heard of him? Me neither.

It’s rare that I come across a writer, fiction or nonfiction, completely unknown to me and without a single Google or Wikipedia reference. But that is the case for Mr. Kaunitz. No listing. Not a single sentence. Not even a passing reference in someone else’s story.

Here’s the book’s title page:

The World Publishing Co. (New York and Cleveland) originated in 1902 as a bookbinding company and its main years of operation were between 1940 and 1980.

In mid-20th century the company could boast a pedigree of big name authors, Robert Ludlum, Michael Crichton, Ayn Rand, Raymond Chandler and Simone de Beauvoir, to name just a few. It was also the first publisher of Eric Carle’s A Very Hungry Caterpillar and, at one point, the world’s largest publisher of the King James Bible.

Thanks to Wikipedia, much can still be found about the now defunct company. The Times Mirror Company eventually acquired World Publishing (in 1962), by which time, it was producing 12 million books a year, one of only three American publishers to produce that much volume.

In 1974, Times Mirror sold it to the U.K.-based Collins Publishers. Finally, in 1980, Collins broke up World Publishing, selling its children’s line to the Putnam Publishing Group, the dictionary line to Simon and Schuster, and otherwise ridding itself of World’s assets.

Back in 1940, however, World was thriving, introducing a new 49-cent hardcover line called Tower Books.

A Popular History of Philosophy was one of those first titles, coming out in 1941. Let me repeat that date. 1941! Not an auspicious date for any new publication on philosophical matters, although one might also suggest that, in a time of great turmoil and distress, such a book was badly needed.

Timing, it is said, is everything. Soon enough, all minds in America were to be focused on matters of greater urgency, like winning another world war. Maybe that’s why the book and its author disappeared from view.

Having an inquisitive mind, it wasn’t long before I set off on a search for answers.

First off, I went online to see if the book can still be purchased. The answer was a resounding yes.

A new 2012 edition can be found on Amazon (a leather-bound copy for $71.33 and a paperback for $39.95) and a digitized version exists on line, courtesy of Google and the University of Michigan library.

AbeBooks also has a second title for Kaunitz: Philosophy for Plain People, published in 1926 by Adelphi (New York) – for $20, plus shipping (hard cover; “good condition, no dust jacket”).

But that’s it. Amazon provides no detail on the author and just one garbled review. The book itself includes no acknowledgments, no biography, no indication of any background whatsoever (not even an academic position at a college or university, respectable or otherwise).

Only one reference in the book exists to any other person, a Cornell professor who served as a mentor, Frank Thilly, whose History of Philosophy “served as a guide throughout this work” (p. 366). And a dedication (“affectionately” dedicated, no less) to the author’s two sons, both unnamed, but of whom it is hoped the book will help them “attain the highest ethical and moral life”.

I wondered whether Mr. Kaunitz had erred not just in the timing of the book’s release but also in what he preached. But no. Unlike some of his time who, in the late 1930’s, flirted with the darker side of nationalism and fascism, and have been appropriately condemned to the political/literary dust pile, Kaunitz did not hesitate to take up the cudgel against the then predominant Nazi menace. Here he is talking about Oswald Spengler (p. 373):

“It is most likely that Spengler was influenced in his pessimism by his two countrymen, Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, when he predicts the eclipse of Western civilization.

“Two decades after the publication of his book [The Decline of the West] he might be forgiven if he were to indulge in furtive ‘I told you so!’ For, at the behest of a misleading ‘Fuehrer,’ the Prussian spirit has again placed its stamp upon the German people. And yet, it can be said that civilization which has survived many another onslaught, will go on in spite of all the mistakes that have been and will be, made.

“Better leaders will reappear, saner counsels will once more prevail. And whereas in an earlier day the darkness that descended upon the peoples could last longer precisely because of circumstances, it is safe to say that in this later period of the history of civilization … the interplay of minds [will] shorten the present error of ill-will and barbarism… forced upon mankind, first by one dictator, then by another.”

Although a trifle wordy (and I admit to shortening his text), his key point is just as accurate eighty years later.

Kaunitz then goes on to reflect on the power of mass communications, “the foremost of which [in 1941] is, of course, the radio. True, the propaganda machine in… authoritarian countries misuses this medium, but the truth cannot be kept out forever, and sooner or later dictatorships destroy themselves.”

His words of praise for Sigmund Freud and personal regret at Freud’s “banishment” from his native Austria (pp. 368-9) would seem to confirm the author’s liberal views. He finishes up the book (Chapter 20, entitled A Plain Philosophy) with his own statement of principles, espousing “ethical living” and a righteous approach to life (p. 378).

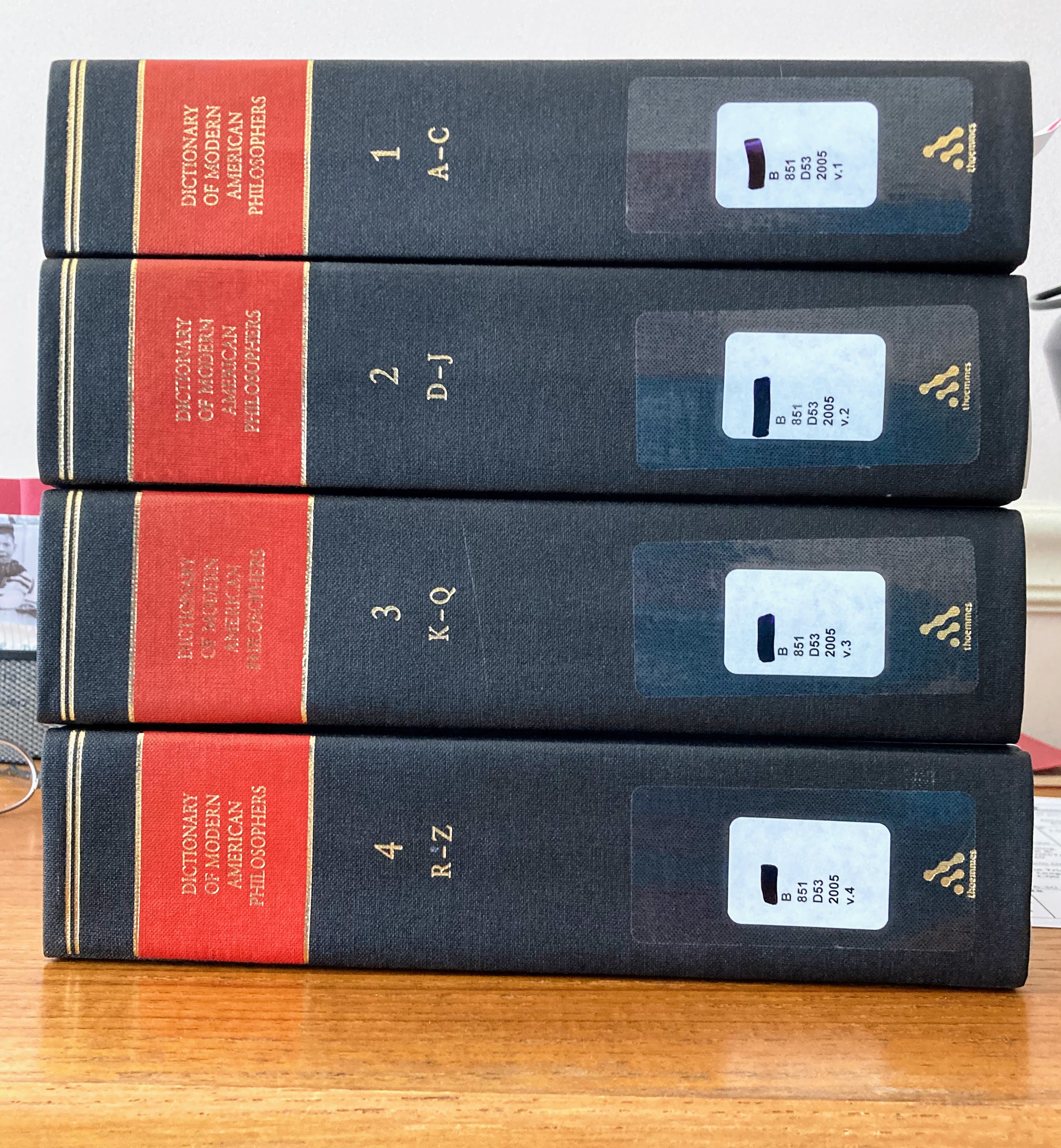

A second search for Frank Thilly led me to The Dictionary of Modern American Philosophers, a four-volume work (2697 pages!) covering the period 1860-1960. It was first published in 2005 by Thoemmes Continuum, Bristol, England (John Shook, General Editor), with the ebook now selling on Google for $1150.57 (CDN). The ambitious dictionary contains 1082 entries by 500 authors, providing an “account of philosophical thought in the United States and Canada” over 140 years.

The first 800 pages of the dictionary are available on Google for preview. Unfortunately those 800 pages took me only to the letter F, well before the K or the T.

A more exhaustive search of the Google site for Frank Thilly noted four listings and page numbers but provided no further access. A similar search for our mysterious author turned up nothing.

But I wasn’t done yet. I contacted two local library systems, the Vancouver Public Library and the Fraser Valley Regional Library, to see if either one could help. The former did come through, providing an interlibrary loan of the dictionary’s four volumes, courtesy of Lakehead University (https://www.lakeheadu.ca/), Thunder Bay, Ontario.

Frank Thilly (1865 – 1934) does get a mention (a little over two pages of text, pp. 2399 – 2341). A scholar of German, philosophy and political economy, he studied in Cincinnati, Berlin and Heidelberg and taught philosophy at Missouri, Princeton and Cornell, staying in Ithaca, New York, from 1906 until his death.

According to the listing, rather than formulating a “thorough-going philosophical system” (p. 2400), Thilly dedicated himself to the profession, writing several books and papers, translating several German works into English, authoring in 1914 a widely-used philosophy textbook (in print for six decades thereafter and of which Mr. Kaunitz clearly made good use), taking leadership positions of academic associations and acting as editor of several journals.

All in all, the professor receives high praise for his “commitment to ethics and social philosophy”, his defense of “rationalism and idealism” and his “extraordinary mastery of the history of western philosophy” (p. 2400).

But what about Mr. Kaunitz? Unfortunately, he gets nary a word. In the end, my search proved fruitless. (Any ideas, readers?)

That being said, I can’t let Mr. Kaunitz go without one last observation. His Popular History is not one of those Eurocentric tomes, beginning with Socrates, taking us through Christianity and the Enlightenment and ending with the 20th century philosophers.

In fact, Kaunitz looks far and wide, starting with pre-recorded history, a time of ancestor worship and world origin stories, and examining the religions of India, the Middle East and China.

He was a man of his time to be sure, but certainly fair-minded and forward-looking. In sum, there’s much to praise here, especially for a scholar who’s completely disappeared from public consciousness.

You must be logged in to post a comment.