Sometimes unexpected books arrive in one’s life. From surprising sources. Through unlikely routes. About subjects one never usually reads. And then, once started, one is compelled to read right to the very end and, finally, write about.

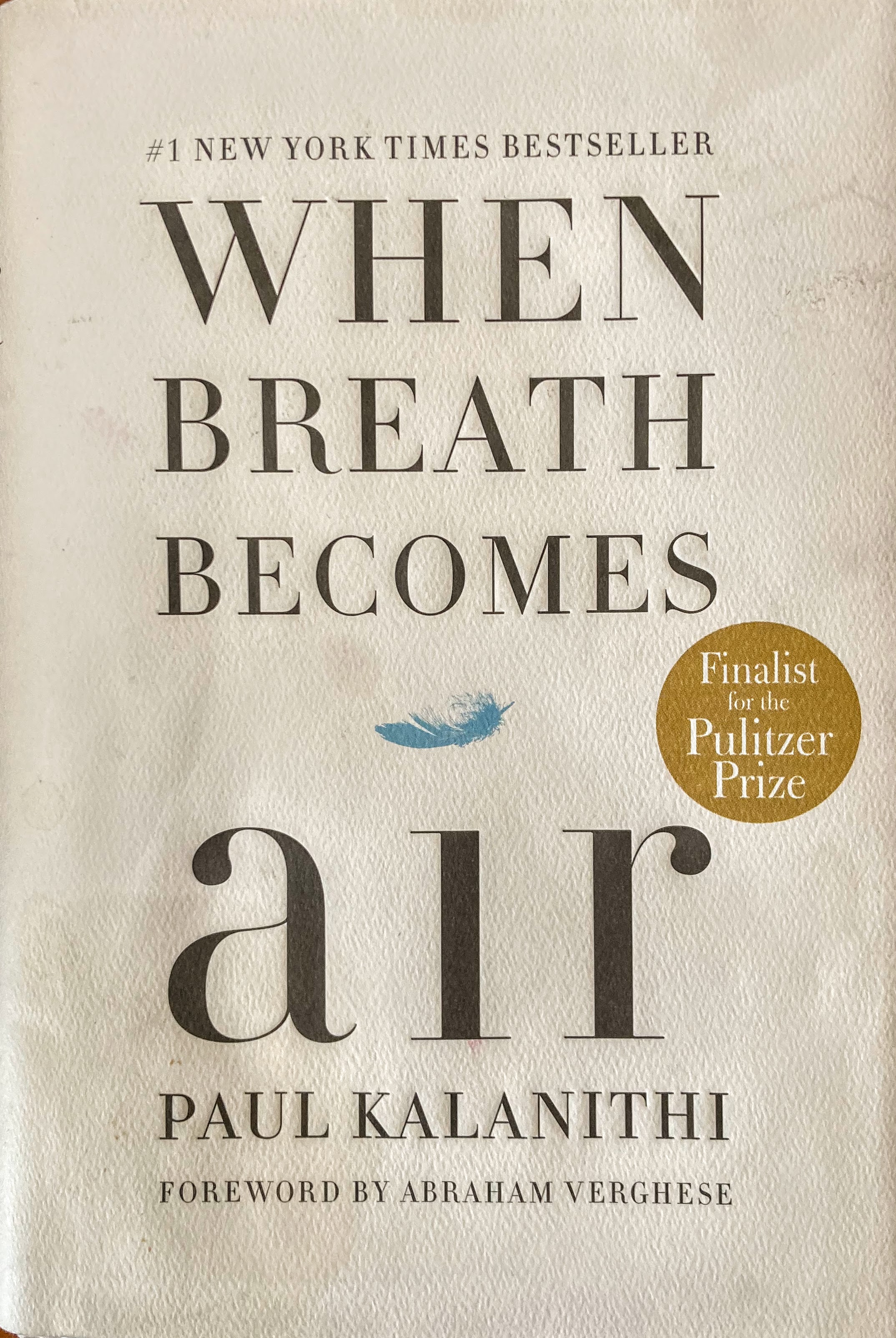

Such was the case for When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanthi. The book recently travelled from my grandson to his mother to me. The book’s subject is life and death, but mainly about the latter, and the question posed is: what makes life worth living when faced with fast approaching death.

I had not heard of the book, which, according to the cover, was a finalist for that year’s Pulitzer Prize. It’s not a long read, a mere 225 well-spaced pages. But it’s certainly compelling. My daughter completed her reading of it during a plane ride across the country.

Random House, New York, 2016

Dr. Kalanithi was a neurosurgeon, who came to medicine only after degrees in Biology and English literature. He had a great love of and talent for writing (make sure to read the forward by Abraham Verghese), easily discernible by the quality of the prose.

Kalanithi describes at length his university studies, the jump from literature to medicine, the decision to become a neurosurgeon, life in medical school, the unrelenting demands of the profession, dealing with the life and death of patients and finally the unexpected CT scan results that demonstrated his advancing cancer. It had already “invaded multiple organ systems…The prognosis was clear.”

He turns to fiction in an attempt to understand his impending death. “Lost in a featureless wasteland of my own mortality, and finding no traction in the realms of scientific studies, intermolecular pathways and endless curves of survival statistics, I begin reading literature again.” (p. 148)

Kalanithi reads Cancer Ward (Alexander Solzhenitsyn), The Unfortunates (B.S. Johnson), Ivan Ilych (Leo Tolstoy) and Mind and Cosmos (Nagal). He also turns to Kafka, Woolf, Montaigne, Frost, Greville and the memoirs of cancer patients – “anything by anyone who had ever written about mortality”, searching for a vocabulary to “make sense of death”. (p. 148)

Inevitably, in a book about death – about accepting that fate and dealing with it as best one can – only one outcome is possible. The reader gets the full sense of the chemotherapy treatment, the thankful period of remission, the grabbing of the rare opportunity to get back to work and the operating table and, ultimately, the devastating follow-up CT-scan that shows the reoccurrence of the disease. The final downward trajectory ensues.

Prognosis to death lasts a mere 22 months, and in that time the joys of family (“simple moments swelled with grace and beauty, and even luck”, p. 218), especially the birth of a daughter, are not ignored. The last chapter, an epilogue, is written by Paul Kalanithi’s widow, Lucy. It is no less compelling, no less moving, no less satisfying a read.

This book is not just a moving testament about death, it is about time, learning and love. I recommend it highly.

One more quote from that epilogue is worth repeating: “Paul’s decision not to avert his eyes from death epitomizes a fortitude we don’t celebrate enough in our death-avoidant culture…He spent much of his life wrestling with the question of how to live a meaningful life, and his book explores that essential territory.” (p. 215)

His journey, his widow declares, was one of transformation, from one passionate vocation to another, from husband to father, and finally…from life to death, the ultimate transformation that awaits us all.

I might also add the transformation to published author. As Lucy Kalanithi ultimately notes, “Paul was proud of this book, which was a culmination of his love for literature…and his ability to forge from life a cogent, powerful tale of living with death.” (pp. 220-21)

& & &

On another note, I cannot ignore the passing of Canada’s greatest short story writer, Alice Munro, who died May 14 at the age of 92. (And believe me, given the wealth of literary talent produced in this country, there’s heavy competition for that title.)

Her very first collection of stories (1968) won the Governor-General’s Literary Award; in 2013 she was awarded the Nobel Prize for her entire body of work. In between, her stories were often to be found in The New Yorker, the Atlantic Monthly and Paris Review. Here’s a link to her books on Penguin Random House, her longtime publisher.

Since space doesn’t permit a worthy review of her life and contribution to literature (by my count, 14 short story collections and 20 awards), here is one from Time: https://time.com/6977937/alice-munro-dies/. From that tribute, let me quote Jonathan Franzen, who in the New York Times reviewed her 2004 story collection Runaway:

“Reading Munro puts me in that state of quiet reflection in which I think about my own life: about the decisions I’ve made, the things I’ve done and haven’t done, the kind of person I am, the prospect of death.”

Given the subject of this post, it seemed the most appropriate of so many accolades.

You must be logged in to post a comment.