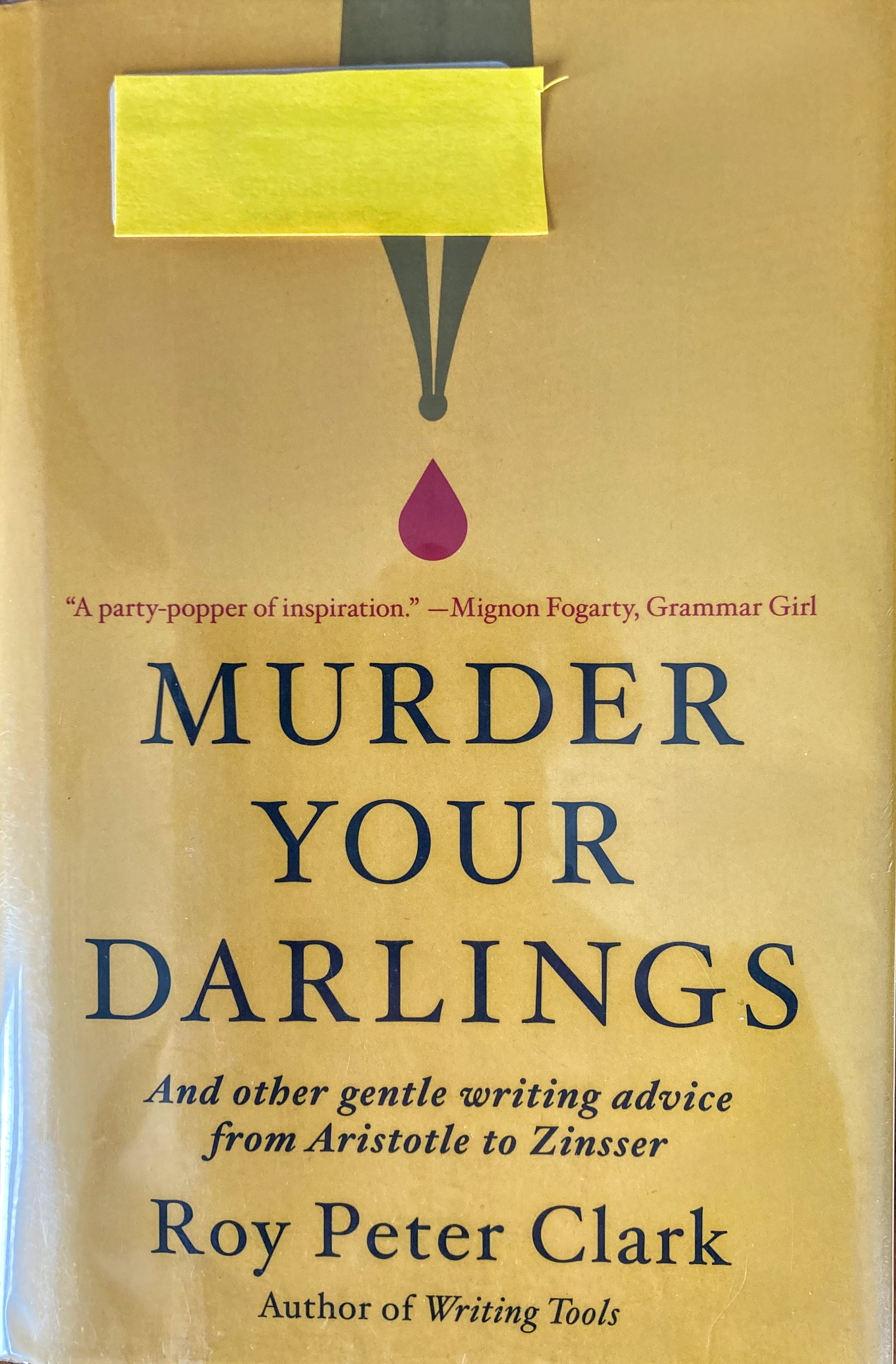

Every aspiring author – and certainly anyone whose bothered to take a creative writing course – has heard this sage advice. But only recently did I come across a book with the title.

I’d like to say I’d read it and taken all the advice offered before beginning The Ravenstones series, but since the book was only published in 2020, any such claim would be impossible.

I discovered Roy Peter Clark’s publication on a recent foray to my local library. Couldn’t help but pick it up to see if I’d been doing the right things all the way along. Or at least some of the right things.

New York: Little Brown, Spark, 2020

Clark goes all the way back to Ancient Greece and Rome to come up with a synthesis of the best advice ever prescribed to aspiring writers. (I imagine it wasn’t long after the first person dared to etch a thought with a stylus onto a clay tablet that some hard-hearted critic came along with an opinion on how to improve the work!)

A teacher of many years, Clark knows how to get a point across in short order and with maximum appeal. He provides 32 sets of succinct advice from prominent writers or teachers (with takeaway lessons) organized into six sections: language and craft, voice and style, confidence and identity, storytelling and character, rhetoric and audience, mission and purpose.

Each chapter is brief, usually no more than eight pages in all. The names of most contributors will be familiar to readers: George Orwell, Kurt Vonnegut, Tom Wolfe, Stephen King and E.B. White, 43 in all. One Canadian is included: Northrop Frye (Fables of Identity: Studies in Poetic Mythology). And Clark does not forget the originator of the phrase, “murder your darlings”, Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch.

Each section begins with a two-page introduction of the topic and of the advice provided. Each subsequent chapter leads off with a sentence or two encapsulating the key point. Some guidance is simple and straightforward; other lessons are more eloquent.

Here’s a sampling:

- Vary sentence length to create a pleasing rhythm. Think of each period as a stop sign.

- Write for sequence, then for theme. Readers want to know what happens next and also what it all means.

- Become the eyes and ears of the audience. Write from different visual and aural perspectives. From a distance and up close.

- Distill your your story into five words – maybe three. Use the ‘premise’ or other tools to articulate what your work is really all about.

- Write to make your soul grow. Transform the disadvantage of suffering into the redemptive advantage of powerful writing.

Next comes the name and author of the work in question, a toolbox (essentially an explanation of the key points). Ending each chapter are suggestions to improve output, such as “identify the bruise on the apple” to round off a character.

For anyone who’s yet to grasp the gist of “murder your darlings”, it means to get rid of (i.e. kill off) those clever words and brilliant phrases the writer loves the most but – if he or she is being truly honest – add nothing to the story.

Thankfully, Clark doesn’t insist on forsaking them forever. Such brilliance, he declares, can always be saved for another time and context.

I picked up several takeaways, but if I had to choose two, they would include the following:

- the learning never stops, no matter the age:

Here, Clark quotes the sculptor, Henry Moore: “The secret of life is to have a task, something you devote your entire life to, something you bring everything to, every minute of the day for your whole life. And the most important thing is – it must be something you cannot possibly do.” (pp. 103-104)

- revision is an essential part of the process:

The word revise comes from the French, reviser, which means “to see or behold again” (Shorter OED, Vol. 2, p.1821). “No one writes the perfect story, one perfect word at a time…With experience, you will learn that early writing is not sculpture, but clay, the stuff in which you will find the better work.” (p. 108)

Wise counsel, indeed. Murder Your Darlings is a profound book and great read. Highly recommended for journalists and writers who wish to up their game and for those who simply love exploring the writing process.

&&&

An update on my post of March 2 regarding the death of Flaco, the Eurasian eagle-owl (Flaco is Dead. Long Live Flaco.) New York’s beloved zoo escapee was found dead on a city street back in February. According to various news sources (in this case patch.com), “Flaco’s wings and other tissue samples were taken to the American Museum of Natural History to become part of its scientific collection following his March necropsy, which found high levels of “debilitating” rodenticide in his body.”

So, after all, the poor bird will live on. Well, at least in some fashion.

You must be logged in to post a comment.