Every year in Canada, Nov. 5 to 11 is Veterans’ Week, an opportunity for Canadians to honour the efforts and sacrifices of our veterans. November 11 marks Remembrance Day, the final day of Veterans’ Week, and recalls the end of hostilities during the First World War, on that date in 1918.

Back in the early 1970’s I was a young officer serving in Canada’s Armed Forces, in an Air Transport squadron (412) based in Ottawa, to be exact.

Having injured my left knee during my annual fitness test and in need of an operation, I was admitted to the National Defence Medical Centre (NDMC), where I stayed for a few weeks, first, for the surgery and, then, the rehab. In between treatments I would get around the huge multi-story hospital in a wheelchair.

Aside from the physiotherapy and the pleasure of reading, daily life was pretty dull. Even I can only read and rest so much. As a result, every chance I’d get I would leave my bed and room, riding out and exploring some of the other wings and floors.

One day, as the elevator doors opened and I wheeled myself out onto an unexplored floor, I realized that I had chanced upon the veterans’ ward. But not young veterans; these were the very aged and infirm ones, those needing constant care within the confines of a hospital.

Remember this was the 1970’s: I’m talking about veterans of the First World War, not the Second. At best they would have been all in their late 70’s, but more likely 80’s and beyond.

A small coterie of these vets sat in wheelchairs just like mine, circling the bank of elevators, staring blankly into space or at the incoming visitors or patients. In other words, since no one else happened to get off, at me. As I exited the elevator and its doors closed behind me, I felt like a trapped animal.

No one spoke; no one smiled; no one made a motion. They just stared at me. It was the most intimidating, uncomfortable, unnerving experience I’d ever encountered. I couldn’t wait to escape.

But, of course, being trapped in a wheelchair, I couldn’t leave until one of the elevators returned. As I turned my chair around to face the elevators, with eyes boring into the back of my head, the wait seemed to take an age and a half. Finally, the doors opened and I beat a hasty retreat to the sanctuary of my own floor.

To this day, I regret my hasty action, wishing I’d the presence of mind to try to talk to one or two of them.

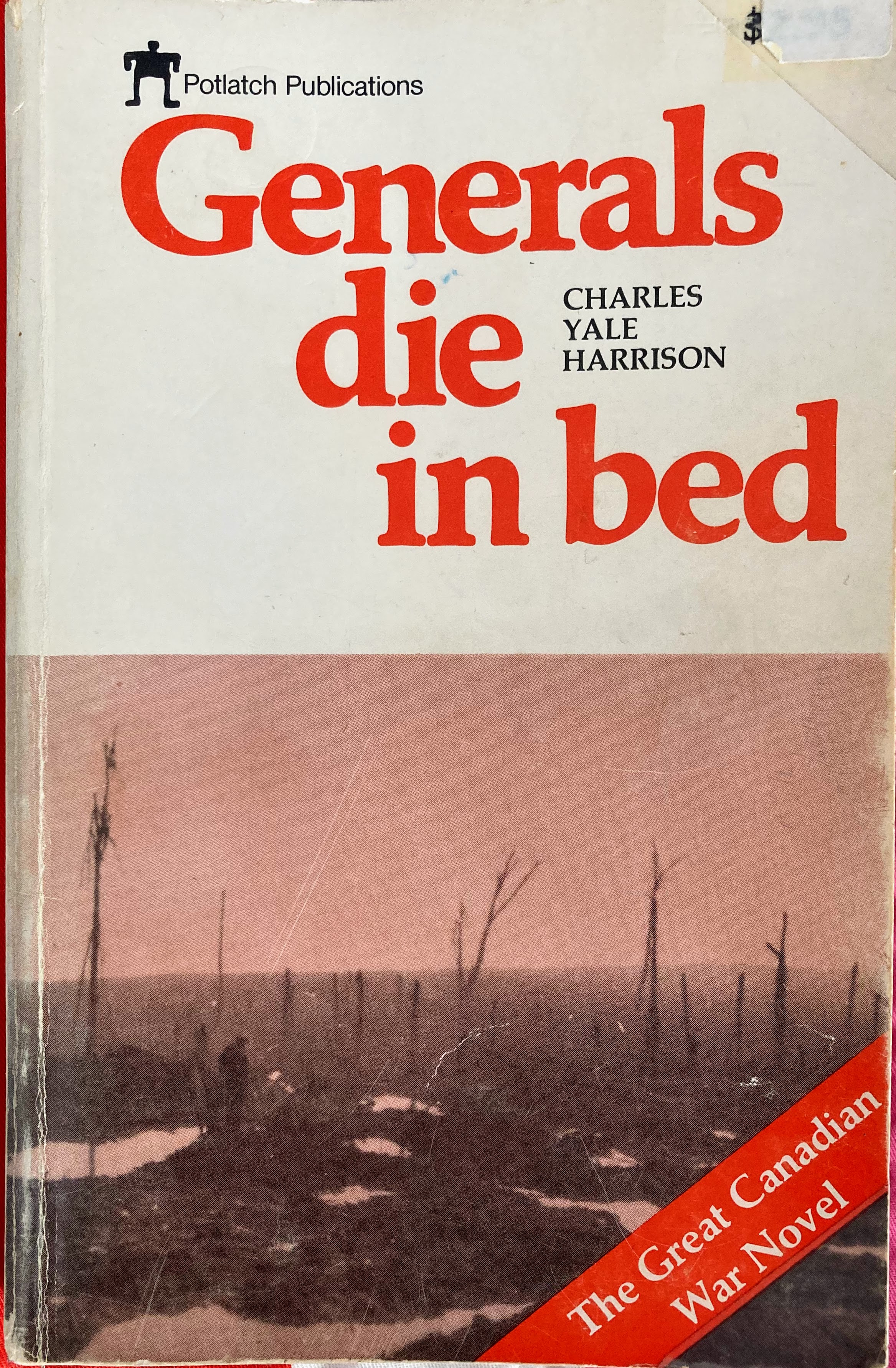

I was reminded of this event upon reading a book my son-in-law lent me earlier this year. Generals die in bed, by Charles Yale Harrison, was originally published in 1930. My son-in-law is a journalist who shares my interest in things military and in the First World War in particular. He spoke about the impact this book had upon him and, when originally published, its impact upon the world.

Hamilton: Potlatch Publications, 1975

Charles Yale Harrison was a man of many hats, straddling the line between Canada and the United States throughout his life. Born in Philadelphia in 1898, he spent his formative years in Montreal, where his journalistic ambitions took root.

He even landed a job at the Montreal Star at the young age of sixteen. However, the outbreak of World War I put his burgeoning career on hold: Harrison enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force and served on the Western Front, where he was wounded during the Battle of Amiens.

After the war, Harrison set his sights on New York City, where he carved out a successful career, working as a novelist, journalist, and even a public relations consultant. Despite this diversity, Harrison’s legacy is primarily defined by his books, especially his powerful 1930 novella, Generals die in bed, an indictment of war and the glorification of military leaders. This anti-war masterpiece remains a significant work of fiction, even today.

1930 was quite the year for war memoirs and novels. In addition to Generals die in bed, several more came out. Goodbye to All That (Robert Graves), All Quiet on the Western Front (Erich Maria Remarque), Memoirs of an Infantry Officer (Siegfried Sassoon) and Farewell to Arms (Ernest Hemingway) all became bestsellers.

Perhaps it took a decade for those exposed to the war’s horrors to put their thoughts onto paper and, then, for publishers to realize that the public would accept its painful reality. Possibly, as the “roaring twenties” giving way to worldwide depression and the “dirty thirties”, the public was ready for the change in mood.

As the title indicates, this book does not celebrate great battles or heroic assaults against a dreaded foe. It focuses more on daily life in the trenches, a “muddy wasteland, crawling with lice and rats, littered with stinking, decaying corpses, laced with fearful creatures hurling death machines”.

When not living with the daily stress of mere existence, the author is ordered into No Man’s Land to do battle or relishes brief respites behind the lines or, more rarely, a glorious leave in London. His real horror comes in encountering the enemy and in realizing that his foe, although just as young and afraid, must be killed in the most brutal of fashions. Comedy and dread are intermingled often; the throbbing of artillery ever-present; death often comes without warning.

Although an international best seller at the time, in Canada the book was controversial for its scenes of Canadian soldiers’ looting and killing unarmed Germans. I gather no proof of such claims exist.

Finally, as Wikipedia notes, according to the BBC and contrary to the book title’s claim, more than 200 British generals of the First World War were killed, captured or wounded on the war’s front lines. Given 1500 British soldiers served with that rank, that’s a 13% attrition rate!

*

To my Canadian readers, please don’t miss Monday’s opportunity to recognize veterans of the Canadian Armed Forces and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police for their service, their sacrifice and their ongoing contribution to the community.

Leave a comment