Everyone has their own indulgence or two, either open to the world or perhaps better left behind close doors.

When it comes to movies, my indulgence is film noir from the 40’s and 50’s: Glenn Ford in The Undercover Man (1949), is a prime example (lots of free movies can be found on Youtube).

Where pastries are concerned, my indulgence is the classic cinnamon bun.

My food indulgence is long-standing and certainly no secret, having originated during my Winnipeg childhood thanks to the proximity of two wonderful neighbourhood bakeries, one Dutch, one Belgian.

You can check out my Google reviews of various B.C. bakeries: my current favorite (above photo) is Moore’s Bakery, a Kerrisdale neighborhood institution (since 1930), in Vancouver, B.C.

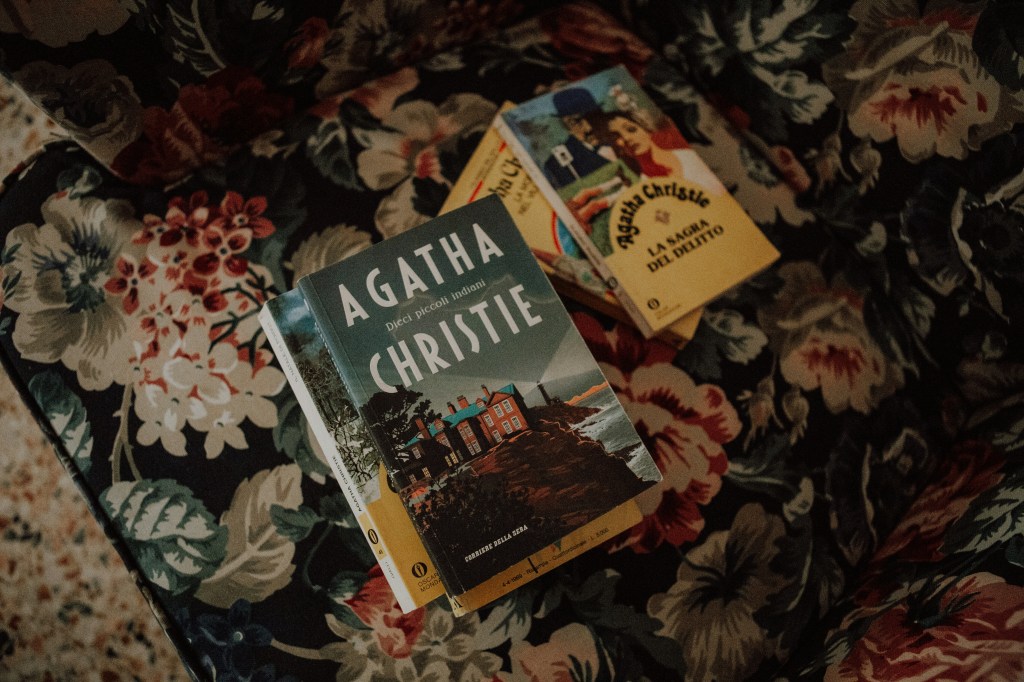

But I even have a third indulgence: the classic English early to mid-20th century murder mystery. You know, Agatha Christie (1890-1976, author of 65 detective novels and 166 short stories), Dorothy L. Sayers (1893- 1957, author of 11 Lord Peter Wimsey detective novels and 21 short stories) and the like (Margery Allingham, Ngaio Marsh).

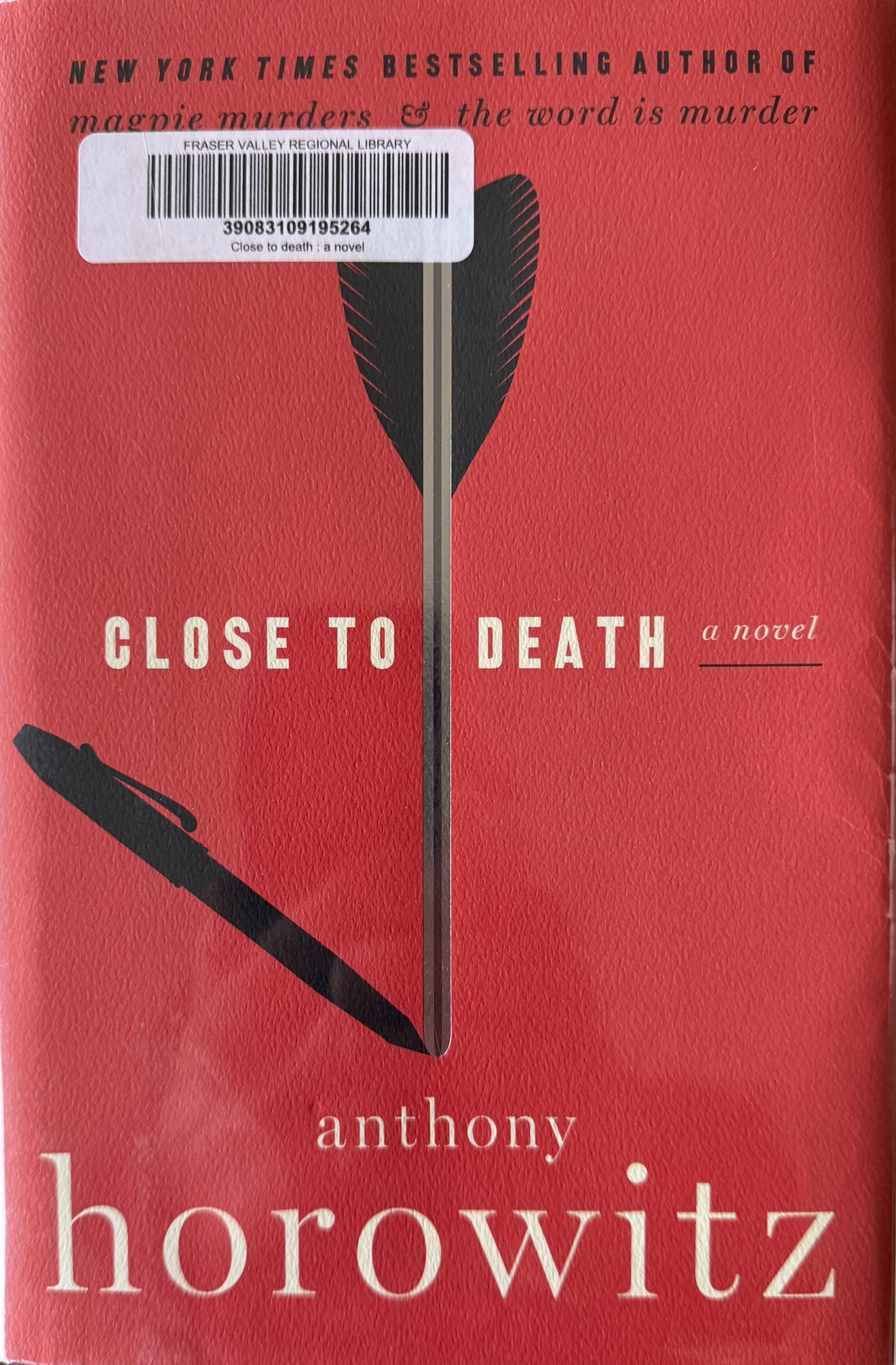

Today, no one is doing a better job of harkening back to that era than the prolific British author Anthony Horowitz, perhaps most famous for his Foyle’s War television series (PBS) or Alex Rider young adult series, the latter both in print and on Amazon Prime.

Recently I came across a recent release, his Close To Death, which I devoured over a mere three days. Not easy, when I have so much else on the go.

HarperCollins: New York, 2024

Horowitz has now written five books in the Daniel Hawthorne series:

- The Word is Murder (2017)

- The Sentence is Death (2018)

- A Line to Kill (2021)

- The Twist of a Knife (2022)

- Close to Death (2024)

and two in the Susan Ryeland/Atticus Pünd series:

- Magpie Murders (2016)

- Moonflower Murders (2020)

What makes both series so special is how Horowitz pays homage to that mid-20th century classic mystery genre while, at the same time, also reinventing it.

In the Hawthorne series, he casts himself as a character—a somewhat skeptical, reluctant Watson to the mysterious and brilliant ex-cop Daniel Hawthorne. Each book is a metafictional, first-person account by “Anthony Horowitz”, documenting a case that he and Hawthorne investigate together.

The Pünd books, meanwhile, are mysteries within mysteries. Modern editor Susan Ryeland investigates real-world crimes that are somehow entangled with fictional mystery novels written by the (fictional) author Alan Conway. Two mysteries within one book, stories with full-on Golden Age pastiches, complete with 1950s English settings, stately homes, and genteel suspects. A critique and a celebration of the genre at the same time.

Both follow the classic crime genre in the following ways:

- Golden Age echoes: The stories often center on closed circles of suspects (à la Agatha Christie), with a final Poirot-style gathering for the reveal.

- Meta and Modern: Horowitz blurs reality and fiction, discussing his real-life writing, career, and even publishers, while solving fictional murders.

- Reinvention of the detective duo: The Watson-Holmes dynamic is flipped; the narrator (Horowitz) is the baffled amateur, while Hawthorne is enigmatic and often irritating.

- Locked-room and fair play clues: These elements, essential to any avid crime reader, delight fans of traditional mysteries.

And that’s where things get especially interesting, because Horowitz isn’t just borrowing from Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers; he’s in conversation with them, both stylistically and structurally.

Here’s a comparison of Horowitz’s crime novels with the work of Christie and Sayers:

Agatha Christie

- A master of the “closed circle” mystery.

- Hercule Poirot: Methodical, intellectual, emotionally restrained.

- Miss Marple: Observant, underestimated, rooted in community insight.

- Deceptively plain prose masking complex puzzles.

- Focused more on story than style.

- Tends to stay out of the characters’ internal lives, focusing on human nature and hidden motives—greed, jealousy, revenge.

- Moral universe exists: the killer must be caught.

- Loves the twist ending—often one that recontextualizes everything.

- Stories are structured around timing, motive, and misdirection.

- Examples: And Then There Were None, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd.

Dorothy L. Sayers

- Plots are looser and more intellectually layered.

- An emphasis on psychological nuance, often philosophical or theological themes.

- Her mysteries sometimes explore morality, class, and gender.

- Lord Peter Wimsey: Aristocratic, charming, deeply introspective.

- Sayers evolves him emotionally over several books— he falls in love, questions his past

- Rich prose, literary allusions, even Latin quotes.

- Characters are more introspective, particularly in later books.

- Romantic elements become more prominent.

- Themes of conscience, justice, redemption.

- Philosophical depth—what is justice, really?

- Examples: Gaudy Night, The Nine Tailors.

Anthony Horowitz

- In the Atticus Pünd stories: pure Christie homage—tight plotting, red herrings, and big reveals.

- In the Hawthorne books: more like Sayers in structure—digressive, character-focused, and openly reflective.

- Uses meta-devices to comment on plot itself—who structures the story and how.

- Atticus Pünd is a deliberate homage to Poirot—Continental, cerebral, often imperious, with a calm dignity.

- Daniel Hawthorne echoes Sherlock Holmes more than Wimsey—but Horowitz (as narrator) is the baffled, often exasperated Watson.

- Like Sayers, Horowitz develops his narrator over time—his fictional self evolves, reacts and reflects on his involvement in the cases.

- Plays with storytelling itself as a theme: who controls the narrative, what is “truth” in fiction, how readers consume crime stories.

- Especially in Magpie Murders and Close to Death, he critiques the genre while embracing it.

- Unique feature: Layers of narrative (e.g., a mystery within a mystery) let him play with and subvert expectations.

- Actually able to replicate the styles of his predecessors:

- The Atticus Pünd stories imitate Christie’s spare, clean narrative voice.

- The Hawthorne stories are more playful and self-aware—leaning into humor, wit, and commentary, like Sayers.

- His own style, meanwhile, is always accessible, but slyly clever and full of genre-savvy tricks.

A Final Thought:

If Christie is the queen of plotting and Sayers the lady of psychological insight and literary flair, then Horowitz is the postmodern heir—he blends their strengths and adds a layer of self-awareness they never used. His books are both tributes and innovations: they feel like comfortable old armchairs with secret compartments.

Horowitz’s crime series are like intricate love letters to the mystery genre:

They balance classic structure (fair play, red herrings, clever reveals) with modern narrative devices (metafiction, dual timelines).

He revives the joy of puzzle-solving and the gentle irony of earlier whodunits, while keeping the pacing and tone engaging for today’s readers.

&&&

To all my readers, whatever your indulgence, Happy Easter!

You must be logged in to post a comment.