More than once I’ve been asked why I chose to write in the fantasy genre, specifically using anthropomorphized animals.

I’ve posted before about the subject, the origins of this kind of literature, my childhood influences and how animals display a range of moral behavior (see posts of Aug. 26, 2020, Sept. 9, 2020 and July 8, 2023).

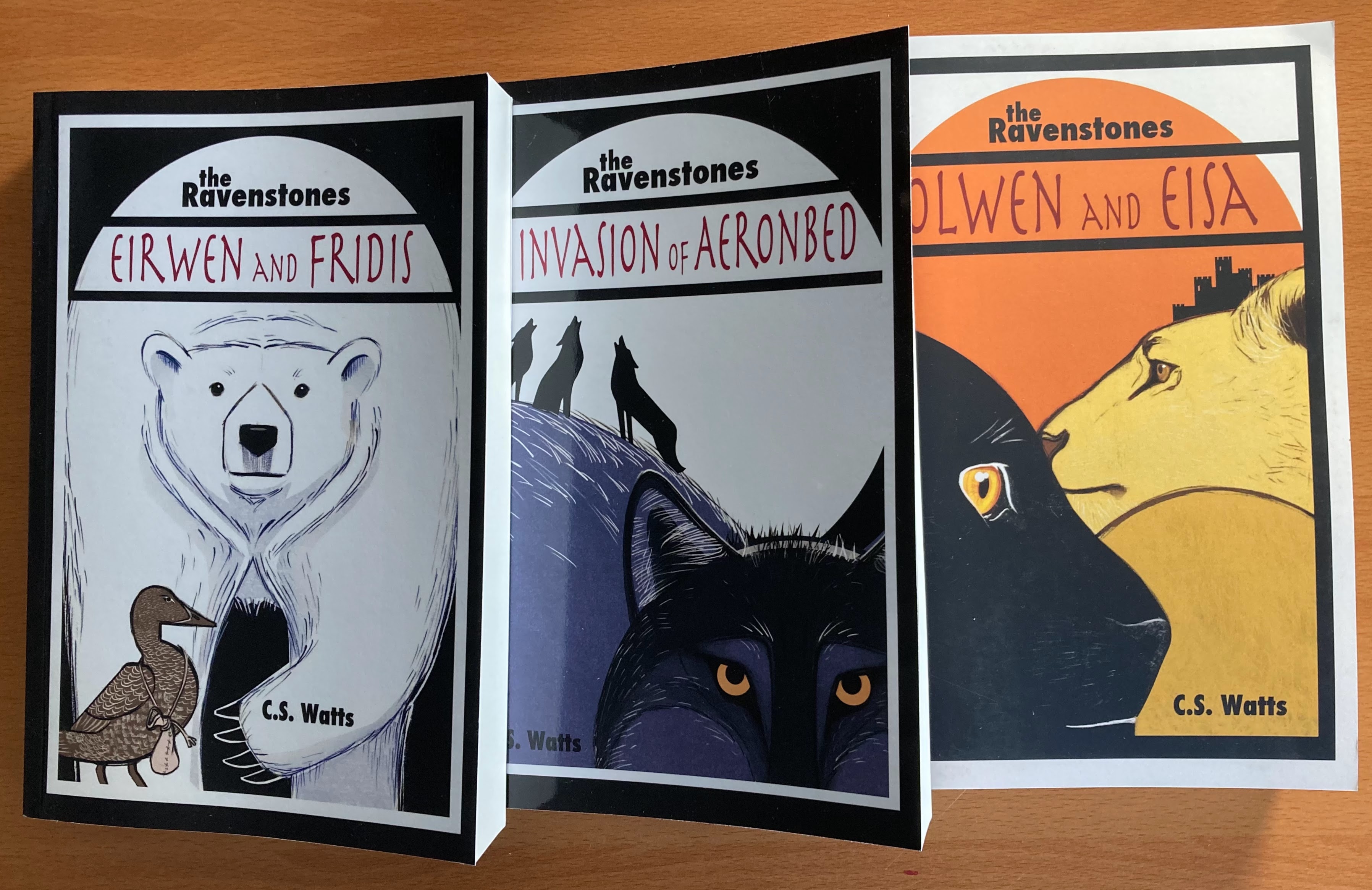

Clearly, the issue resonates with me. Of course, that’s not surprising given The Ravenstones series, with its over 140 animal characters (and not a single human in sight!).

First off, it comes naturally to me to imagine animals who talk and act like humans, whether in a world of their own or shared with humans.

Like most children of my era, I grew up with the classic fairy tales of Aesop, the brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen, all chock full of talking/thinking inanimate objects and animals.

My Anglophile parents raised me on English picture book classics like Beatrix Potter,

comics like Rupert the Bear, on novels like Wind in the Willows and The Jungle Book. Then later in my own reading, I came across the likes of George Orwell (Animal Farm), Richard Adams (Watership Down and Plague Dogs) and C.S. Lewis (the Narnia series).

So, let’s just say it all came naturally.

Next there was the influence of television and one show in particular. Walt Disney Presents owned the Sunday evening time slot (6:00 pm, if I remember correctly); and the animated cartoon episodes were an eagerly awaited attraction for us kids. (I shouldn’t ignore Hanna/Barbera’s Huckleberry Hound and Yogi Bear, which were next in line.)

Today, these cartoon offerings have grown exponentially. The names of the world’s current top grossing animated movie franchises will be familiar to most readers: Despicable Me, Ice Age, Kung Fu Panda, Shrek, Toy Story, Frozen, amongst others. To that list, let me add: The Lion King, Mufasa, Zootopia, Garfield and the most recent Academy and Golden Globe Award winner, the 2024 Latvian-produced adventure, Flow.

Not all animated films are wholly or partly animal-based of course, but a whole lot are. In fact, anthropomorphized animals dominate the genre. According to Wikipedia, the Ice Age series alone has generated $6 billion from its five movies, with a sixth release planned for 2026.

Such global figures highlight the significant commercial success and enduring popularity of these franchises. (I hasten to add my earnings to date come nowhere close to the vast sums these movies generate.)

So, why use animals to tell a story?

Anthropomorphic characters — giving human traits to animals, objects, or even concepts — can bring a great deal to a story. Some of the key benefits are:

- Emotional Connection:

Readers often find it easier to empathize with anthropomorphic characters because they behave in familiar, human ways (talking, feeling love or fear, making decisions). - Simplification of Complex Ideas:

Using animals or objects allows authors to explore deep or difficult themes (like war, society, or mortality) without the story feeling too heavy or preachy. Think of Animal Farm by George Orwell — it’s about totalitarianism, but with farm animals. - Universality:

Humanizing animals or objects can strip away race, class, and other specific markers, making the story more universal. A fox or a teapot can be anyone, from anywhere. - Humor and Playfulness:

Anthropomorphism can add a layer of charm, wit, or absurdity. Funny, talking animals can entertain both children and adults while still carrying strong narratives. - Heightened Symbolism:

Different animals or objects can carry symbolic meaning naturally — a wise old owl, a sly fox, a brave little toaster — helping the author deepen the story without heavy exposition. In The Ravenstones, although I play to type with many characters (yes, the owl) I also go off in different directions. - Creative Freedom:

In the fantasy genre, you’re not bound by realistic human limits. An anthropomorphic character can do wild, imaginative things — fly, shapeshift, live forever — making world-building more fun and flexible. - Safe Distance:

Sometimes it’s easier to talk about tough topics (violence, prejudice, betrayal) through anthropomorphic characters because it creates a slight emotional buffer for the audience.

Here are a few examples, each one using anthropomorphism a little differently — depending on the tone and the message they want to deliver:

- Winnie-the-Pooh (A.A. Milne)

Pooh and his friends deal with emotions like anxiety, loneliness, and loyalty — but because they’re cuddly animals, the stories feel gentle and timeless. - Watership Down (Richard Adams)

It’s about rabbits — but it’s really about survival, leadership, and building a society. The rabbits think and speak like humans, but still behave like real animals in many ways. - The Chronicles of Narnia (C.S. Lewis)

Talking animals (like Aslan the lion) represent deep moral and spiritual ideas. Aslan, in particular, is a Christ figure, but the story remains accessible to all ages. - Zootopia (Disney movie)

An entire world run by animals, where species’ stereotypes mirror real-world prejudices (e.g. the sloth). It’s colorful and funny, but it’s also a sharp commentary on discrimination. - The Wind in the Willows (Kenneth Grahame)

Mole, Rat, Toad, and Badger live in a human-like countryside, dealing with friendship, loyalty, and the pull between adventure and home life. - BoJack Horseman (TV series)

A very modern (and very adult) take: animals and humans coexist, but the anthropomorphic animals are used to explore themes like depression, fame, and failure in ways that hit hard.

Animals can be used in literature in two ways. As animals acting in their normal settings and true to their normal ways (e.g. Watership Down).

Or taken completely out of their natural world, living in what we see as a human world and given human emotions (e.g. Tale of Peter Rabbit, Narnia, Wind in the Willows). In The Ravenstones series I follow the second route.

In the case of Watership Down, Richard Adams tells a story of the threat to the rabbit warren through the perspective of its affected characters. The story would be much different if told by a human observer who objectively describes the animals and their actions.

To write this story, Adams has to imagine the thoughts and feelings of the rabbits as they struggle with their fate. These elements include their limited knowledge of the world around them, their basic biology, and simple behaviors such as running, taking shelter and eating.

In those cases, using animal characters permits telling a story through an artistic lens that wouldn’t be available with human characters and isn’t as engaging.

But that’s not my scene. I use animal characters to tell a human story, in the same manner as C.S. Lewis. Besides bringing to life a great tale, my challenge is to keep it believable by not losing sight of each individual animal’s instincts, attributes, diet and limitations.

Animals in these cases – creatures with free will, moral understanding, and cultural identities – function as full characters rather than simple sidekicks. They can take on a more allegorical role or represent virtues (e.g. loyalty, nobility) or vices (e.g. ignorance, cruelty).

Anthropomorphism, then, allows for an entirely different method of storytelling. While it’s a common practice in literature, it’s just not as well known or appreciated as other genres and writing styles.

Readers will decide in the end whether I’ve been successful or not.

You must be logged in to post a comment.