The title of course comes from the famous 1942 film, Casablanca, words spoken by Humphrey Bogart (Rick Blaine) to Ingrid Bergman (Ilsa Lund) in its closing minutes, probably the second most famous movie quote of all time.

Paris has been on my mind of late.

Perhaps it’s because of President Macron’s current political challenges. Or because I spent time there in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, on several business trips.

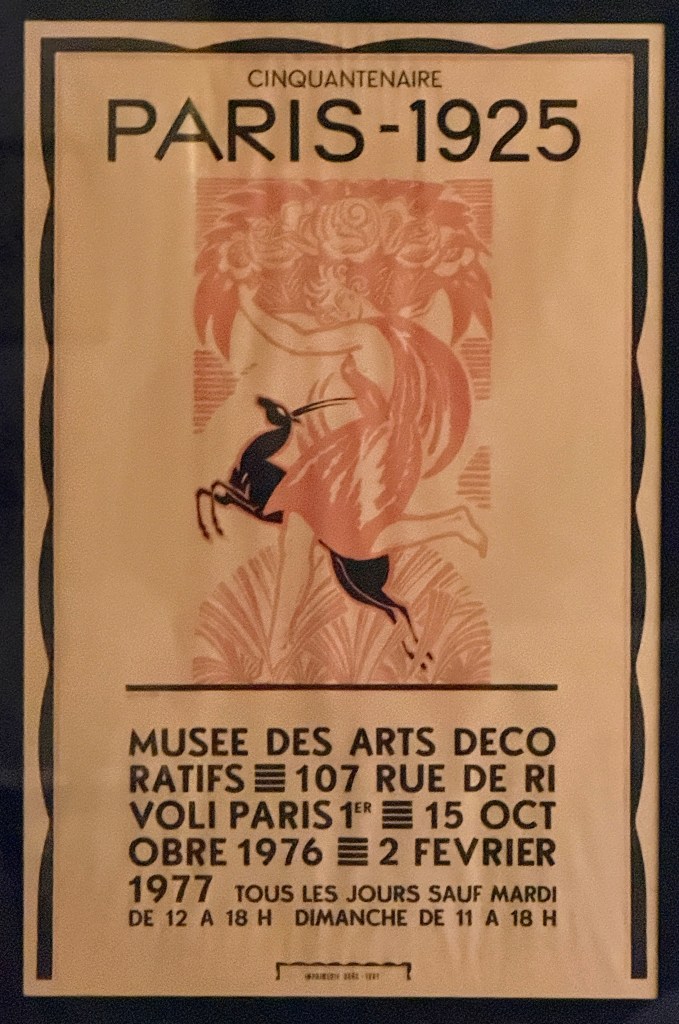

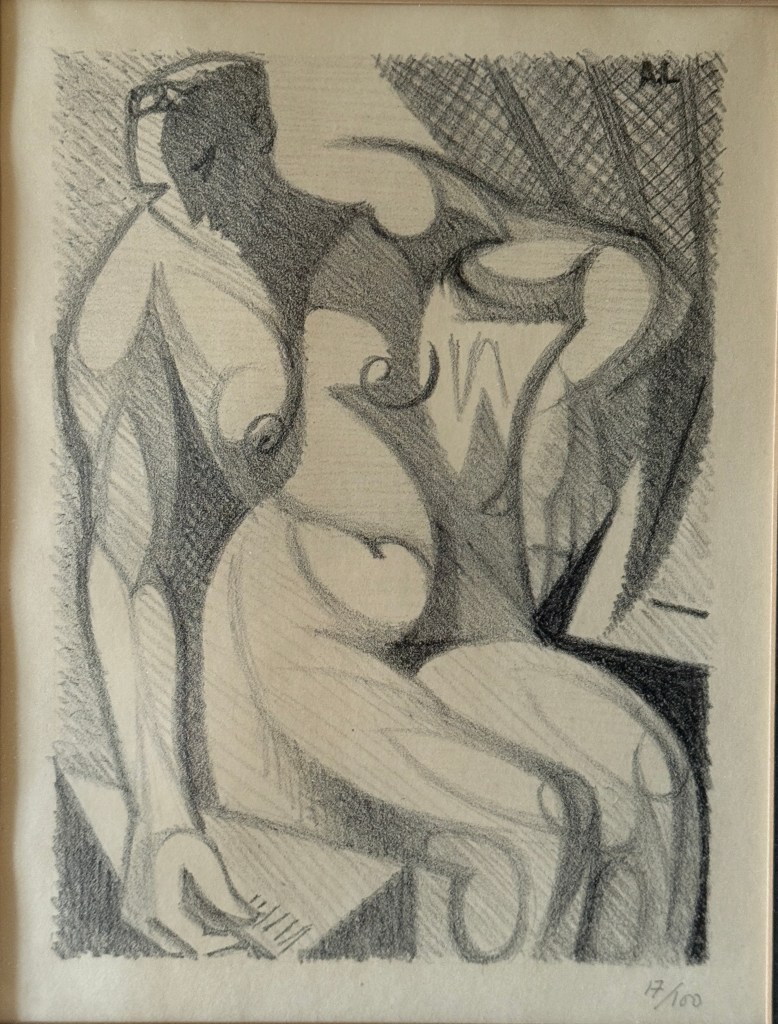

Or perhaps because I purchased several art pieces that adorn the hallway from the bedroom and regularly remind me of my time there.

André Lhote (1885-1962) lithograph

Or perhaps because my daughter just returned from visiting France’s capital, along with Budapest, a city that doubles for Paris when filmmakers need scenes set in mid-20th century and earlier, the city being largely untouched by the Second World War and in the years that followed.

In fact, much of Budapest, especially Pest, was built during the late 19th and early 20th centuries in the same era as Baron Haussmann’s redesign of Paris. Its wide boulevards, ornate façades, neo-classical and Art Nouveau buildings, and stone bridges, along with its numerous cafés, metro entrances, and apartment blocks echo the French capital’s look and create an atmosphere very similar to Paris.

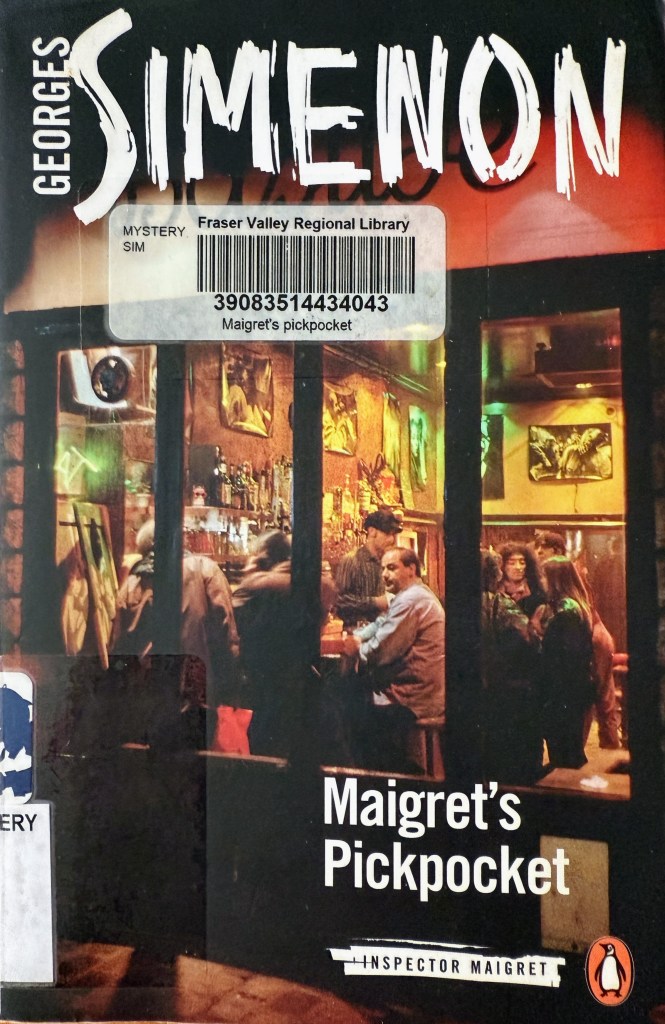

So, with all this in mind, I’ve been reading a few of George Simenon’s Inspector Maigret novels. They don’t take long to read; each one less than 200 pages. But there’s a whole lot of them to read: between 1931 (starting with Pietr the Latvian) and 1972 (ending with Maigret and Monsieur Charles), the prolific Simenon published 75 Maigret novels and 28 short stories featuring the great police inspector.

And alongside this copious production came publications on many, many other subjects: 193 novels written under his own name; 200 others written under 20 or so pseudonyms; four autobiographies; 21 volumes of memoirs.

An average of four to five books a year; 80 pages a day; two weeks to write a book. At his death, world sales stood at more than 500 million copies in 55 languages, written in a vocabulary of no more than 2,000 words.

In 2018, Penguin took on the challenge of republishing all 75 Maigret novels, at the rate of one per month. These are the copies my local library holds.

Penguin Random House; originally published in 1967; this translation (by Siân Reynolds) in 2019

But it’s not just the books, I’ve also been rewatching the British tv series from the early 1960’s, starring Rupert Davies (who was Simenon’s favourite amongst the many actors who took on this role). The programs, 52 episodes over a four-year span 1960-63), are black and white and produced with a modest budget, typical of the day), all available on YouTube.

Series 2; Episode 6; The Lost Sailor, (in French, Le port des brumes); first broadcast on BBC TV, Nov. 27, 1961

In truth, it’s the evocative theme music that pulls me in every time, summoning up the very idea of Paris and taking me back to those days. The piece is called “Midnight in Montmartre”, ironically not composed by a French native but by an exceptional and award-winning Australian composer, Ron Grainer (1922-81).

The Maigret theme won Grainer an award in the UK and made his reputation, leading to a long and successful career composing film and tv scores (e.g. The Prisoner, the 1967 cult classic starring Patrick McGoohan).

Indeed, isn’t it usually an old song or tune, the smell of perfume or baking bread, or the feel of an old photograph that pulls us backward in time? In an instant, we’re no longer in the present but reliving a moment that feels warmer, safer, simpler.

It’s called nostalgia, a word that’s come to signify wistful longing for the past. Yet its history is stranger than its current softness suggests: born in the 17th century as a medical diagnosis, nostalgia was once considered a dangerous affliction.

The story began in 1688 with Johannes Hofer, a young Swiss medical student. Observing countrymen serving as mercenaries across Europe, Hofer noticed how many wasted away far from home. They suffered sleeplessness, melancholy, even hallucinations.

To describe this condition, he coined a new word from the Greek nóstos, meaning “return home,” and álgos, meaning “pain.” Nostalgia was literally the “ache of homecoming.” The Swiss were thought especially susceptible—so much so that the sound of a familiar Alpine cowbell was rumored to trigger breakdowns among soldiers. The only reliable cure, physicians said, was to send the sufferer back to his village.

For more than a century, nostalgia carried this clinical weight. It was diagnosed among sailors lost at sea, students far from families, and colonists adrift in strange lands. To be nostalgic was not seen as a sentimental matter; rather it was to be ill. Homesickness, displacement, and despair were bound together under a single label.

But in the 19th century, as medicine evolved, doctors questioned whether nostalgia was really a disease. At the same time, poets and novelists—especially the Romantics—took the term into their own hands. They used it not just to describe homesickness, but to call up a longing for vanished times and lost innocence.

Gradually, nostalgia was transformed from a diagnosis into a mood, a way of coloring memory with yearning. By the early 20th century, the word had shed its clinical baggage and taken on the wistful glow we know today.

That shift tells us something profound: what once was seen as debilitating has become one of the most appealing and sustaining of human emotions. Nostalgia comforts, connects, and even inspires. It is not a weakness but a resource.

Studies suggest that nostalgic reflection can elevate mood, strengthen resilience, and provide a sense of continuity in the face of change. In other words, nostalgia is not an obstacle to living; it is a bridge.

What makes nostalgia especially alluring is its tendency to polish the past. And of course, memory is selective, and nostalgia often softens the reality. Summers of childhood are recalled as endless play, not mosquito bites; first romances are remembered for their sweetness, not their awkwardness.

In an age of constant digital noise and social upheaval, nostalgia promises a return to “simpler times.” That is why vinyl records, Polaroid cameras, and vintage fashions flourish. These objects are less about utility than about the feelings they carry, the slowness and authenticity they seem to restore.

Beyond comfort, nostalgia helps us understand who we are. Memory shapes identity, and revisiting formative experiences allows us to weave the past into the present. A childhood milestone may later be recognized as a turning point; a painful episode may be softened into a source of strength. Nostalgia is the ongoing process of storytelling by which we give our lives coherence.

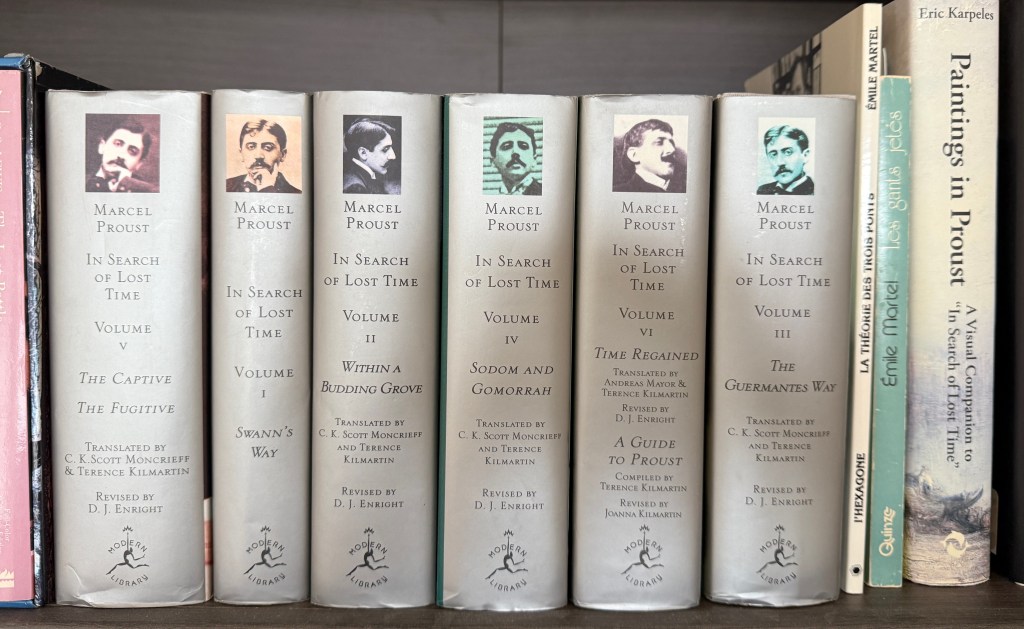

It is also fertile ground for creativity. Writers from Marcel Proust – perhaps the master of looking backwards – to modern memoirists have turned nostalgia into art, exploring how recollection reshapes reality.

Proust’s In Search of Lost Time; also translated as Remembrance of Things Past

Entire industries are built on the appeal of nostalgia: film reboots, retro diners, classic car shows, and advertising campaigns that resurrect long-forgotten mascots. A cereal box design from 1985 does not just sell food; it sells Saturday mornings, cartoons, and the laughter of childhood kitchens. Culture thrives on the recycling of collective memory.

Of course, nostalgia can also mislead. When societies fall into “golden age thinking,” they risk idolizing an imagined past and dismissing the present. Political movements often exploit nostalgia, promising to restore a greatness that may never have existed. On a personal level, too much nostalgia can keep us from embracing new possibilities, turning backward to crave stability, continuity, and roots.

Nostalgia, however, can also look forward, as a way of grounding ourselves in the flow of time. And though it aches, that ache can be sustaining. To recall past joy is not only to mourn its passing but to remember that joy itself is possible. A childhood love of books may inspire an adult to read again. The memory of close friendships may push us to seek new ones. Nostalgia, in this sense, can guide us toward what we most value.

The understanding of nostalgia has traveled far. From pathology to poetry, from disease to delight. Its appeal lies in its richness: it comforts us in disruption, bonds us in community, combats loneliness, romanticizes simplicity, grounds identity, and fuels culture. It can deceive, but it can also inspire.

To be nostalgic, then, is not to be weak or naïve. It is to be human. For memory itself is not neutral but colored, selective, alive. Nostalgia is how we stitch that living memory into the present, assuring ourselves that the story continues, that belonging and joy endure, and that the past, though gone, remains a vital source of strength for the future.

Leave a comment