Earlier this year (April 30) my friend Blake Bobechko published a Substack post about “books for boys”. And just this past week, he let me know that the book in question, “The Boys Book of Adventure“, has been published on Amazon.

As a younger man, naturally Blake’s focus is forward-looking: his concern is for his own sons. As for me, I can’t help but look backwards about my own experience (and perhaps my father’s) with the subject.

Much of the current concern about boys’ reading (or lack thereof) stems from what is deemed to be a “boy crisis”. To quote the New York Times (NYT), of Aug. 15, 2025:

“The school system is struggling to keep boys engaged. Wages have stagnated for men without college degrees. Marriage rates have collapsed in lower-income communities. Job growth is in female-skewed sectors like health care. And the need to provide more social scaffolding for our boys and young men is just as great. We have too many lost boys. Many are in desperate need of positive male role models.”

The early 1900’s, according to the authors of this NYT guest essay, held a similar “boy problem”, in response to which society and policy-makers stepped in to help. I suspect that the offerings my father and I enjoyed and benefited from during our childhood were the results of these interventions.

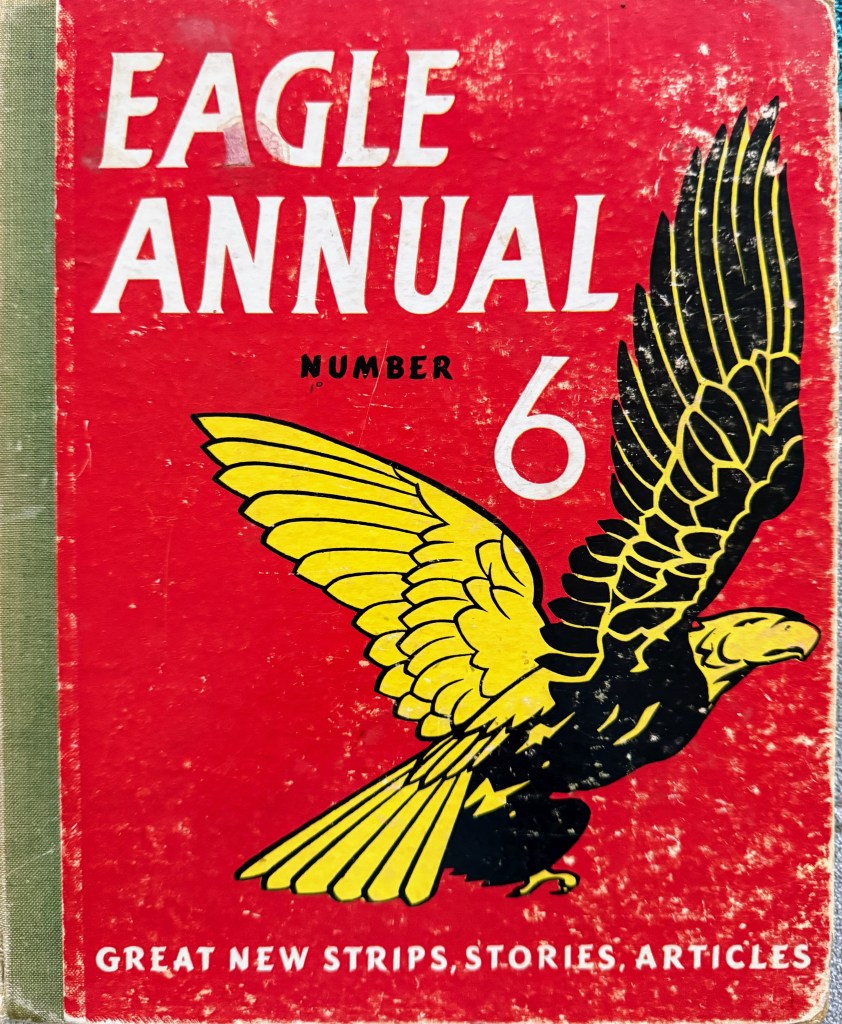

With an English warbride mother, Scottish godparents, lots of UK relatives and few North American ones, I couldn’t help but grow up with a supply of weekly English comics and Christmas annuals for boys. For several years, my favourite was Eagle, which had a pretty good run in the immediate post-war era.

Eagle Annual 0f 1957

When I grew out of Eagle, I made a transition to Boy’s Own Paper (BOP): less cartoons; lot more words; smaller dimension. The BOP’s history was even longer than that of Eagle, but that magazine, too, petered out in that mid-1960’s era, falling victim to changing tastes and economics.

End of an era: five years worth of Boy’s Own Paper, from the early 1960’s (but no annuals)

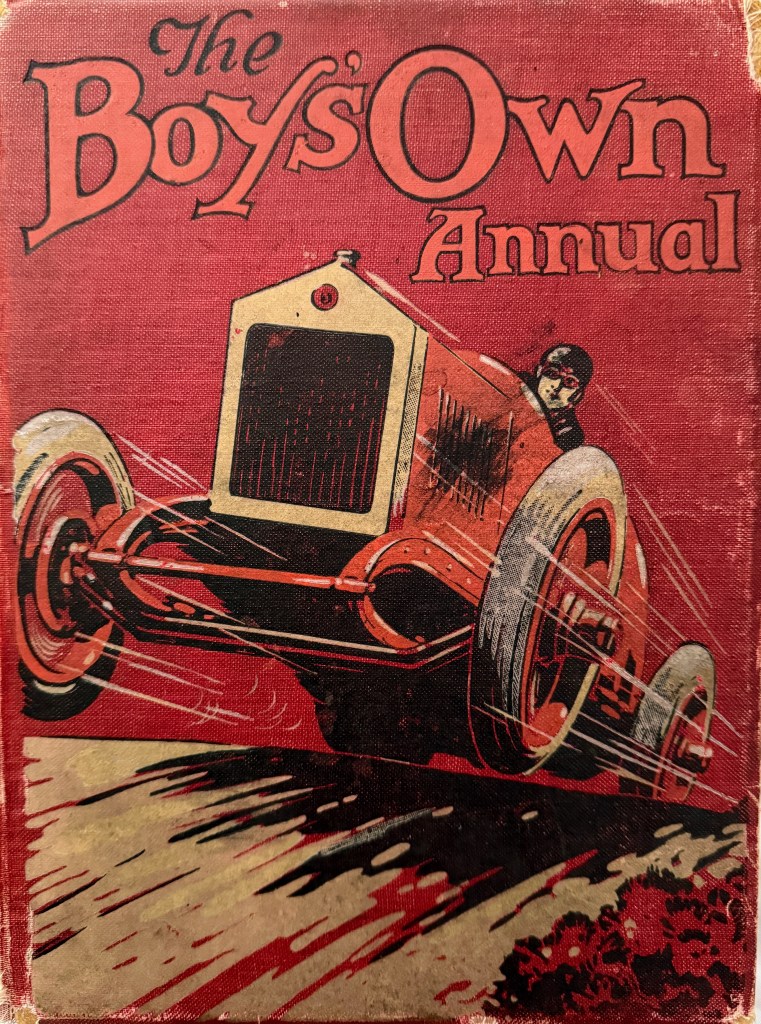

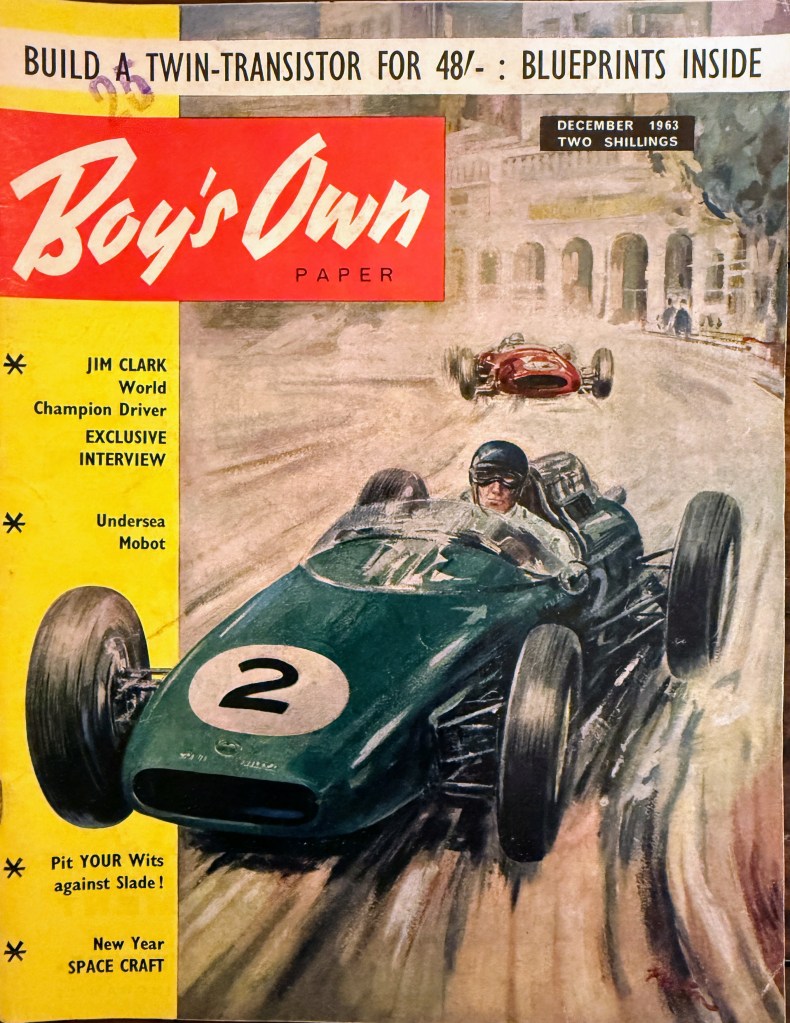

There was an evident formula to these type of publications. Take a look at these two covers, one from 1927 and the other from 1963, and note the similarities:

1926-27 Boy’s Own Annual

1963: Jim Clark, hero to many young boys

What did they contain: adventure stories (usually involving spies), scouting, model-building, puzzles, humor, practical tips for daily life, historical fiction, hobbies (e.g. fishing, chess, stamp-collecting), advice on careers and information on professions, arts and crafts, technology, natural history, facts and figures and the proverbial stories of school boys. And, needless to say, very fast cars!

Both publications had their roots in Christian evangelism, though at very different times: the post-WW2 era for Eagle and the 1800’s for the BOP.

The latter was founded by the Religious Tract Society, a British evangelical Christian organization founded in 1799 and known for publishing a variety of popular religious and quasi-religious texts in the 19th century.

The BOP, one of the society’s many publications, was considered a means to encourage younger children to read and instill Christian morals during their formative years. The first issue was published on 18 January 1879.

The origins of Eagle were more personal: it was started by Marcus Morris, an Anglican vicar, frustrated by (what he saw as) the Church of England’s failed efforts to reach out to youth in the late 1940’s. Its first issue (April 14, 1950) was followed in quick succession by several other similar publications: Girl (1951), Robin (1953, for younger readers) and Swift (1954, for those between the other two).

Eagle was designed as a “respectable” comic for boys, countering the perceived crudeness of American imports. Its serials stressed exploration, ingenuity and a mixture of Christian and imperial values. Fictionalized accounts of explorers, saints and inventors highlighted loyalty, sacrifice and moral choice. Short prose or illustrated tales about schoolboys, sports or war stressed camaraderie, endurance and the just fight against tyranny.

Even swashbuckling adventures carried a moral dimension – themes of honour, duty, service and faith.

Although competitors to Eagle existed, notably Lion, launched in 1952, and Valiant, in 1962, neither really captured my interest.

Unlike Eagle and BOP, which combined comics with written text, these later rivals were completely devoted to comic strips. Even that evolution was not enough. To survive in the new era, they went through several mergers, managing to outlast (even take over Eagle) in the 1970’s, but ultimately, they, too, fell victim to changing tastes and increasing production costs.

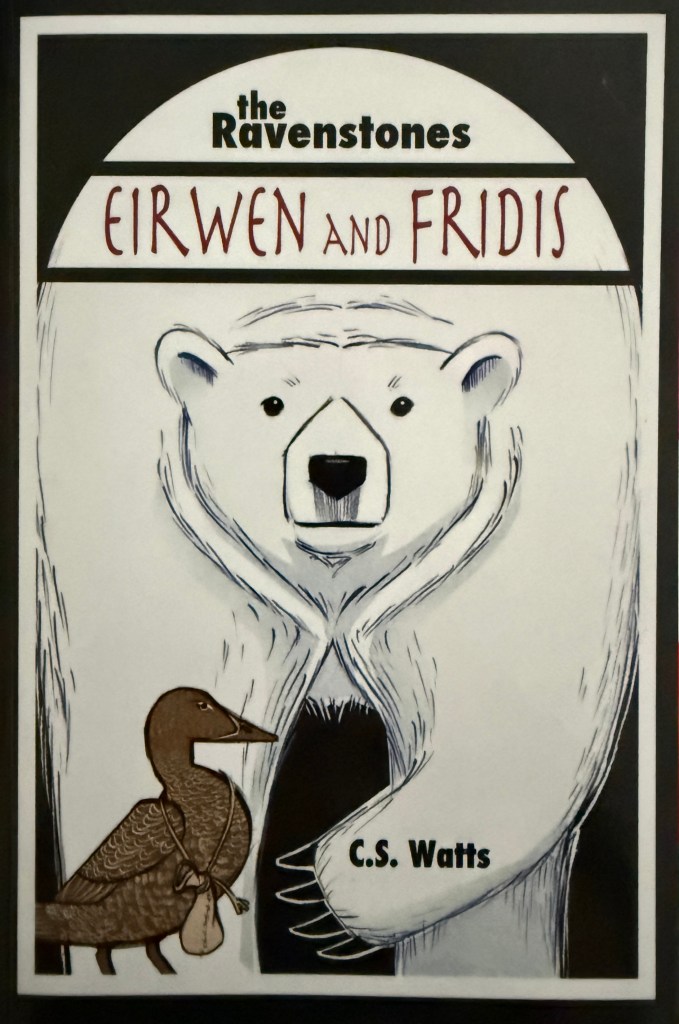

I suspect my writing of The Ravenstones was highly influenced by these weeklies and annuals.

Certainly, echoes exist:

- Heroic but Vulnerable Protagonists

Like Dan Dare, Eirwen is brave yet uncertain, thrust into vast dangers beyond his control. There’s the same blend of individual heroism and moral testing that was at the heart of Eagle adventure tales.

- Moral Weight and Spiritual Undercurrents

The Eagle annuals often layered entertainment with moral instruction. My writing has a similar undertone: the struggles in The Ravenstones are not just physical but ethical and spiritual, where choices matter more than victories.

- Cinematic Pacing and Cliff-Hangers

The annuals honed the art of ending stories on tense notes. I’m currently working on a graphic novel (GN) of Book One (Eirwen and Fridis). Broken into dramatic beats, the GN mirrors this structure — ensuring suspense at key page-turn moments.

- World-Building with Instructional Elements

Just as Eagle inserted cutaway diagrams of spaceships or biographies of heroes, I embed explanatory passages (about Vigmar, Blakfel, etc.) into narrative moments. It follows the same pathway: building immersion and education.

- Allegorical Conflict

The Treens vs. Earthmen in Eagle is not far from Vigmar vs. Aeronbed: both conflicts are pitched as struggles of ideology and survival, filtered through an adventurous narrative.

Reflecting back on these early years, I suspect I’m more indebted to my “books for boys” than I ever previously imagined. Even if only subconscious, the Eagle comics and annuals left me with:

- A belief that stories for young readers can be serious, morally rich, and beautifully illustrated.

- A model of serial storytelling that balances cliff-hangers with reflective passages.

- A framework for heroism rooted in service and duty rather than personal gain.

- A sense that art + text = more than the sum of their parts, a tradition I’m looking to extend in The Ravenstones’ graphic novel project.

& & &

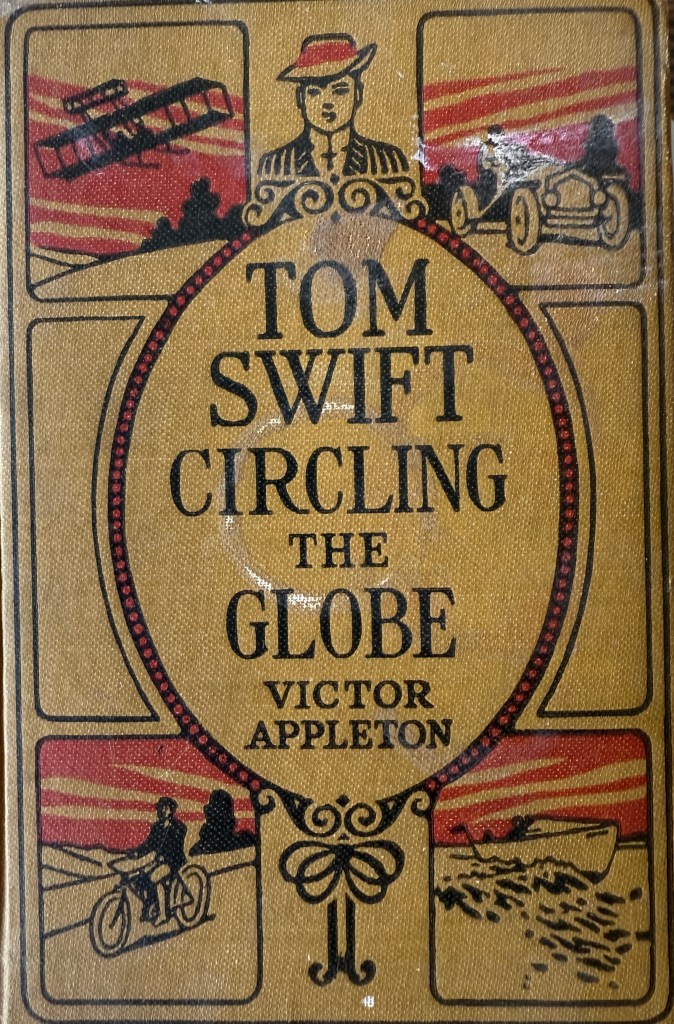

In a future post, I’ll deal with some of the more famous book series aimed at boys; Tom Swift, for example:

Happy reading, whether for adventure or education.

Leave a comment