I can’t believe I’m writing about the NFL for two weekends in a row. Well, not really football; rather about two icons of Latin America. But such is life – we writers find our inspiration everywhere.

Frazer Harrison/Getty Images

It’s been quite a week for Bad Bunny and it’s not over yet: last Sunday at the Grammy Awards, he won Album of the Year for Debí Tirar Maś Fotos (plus two others); this Sunday, he performs at the Super Bowl’s halftime show, which provides the biggest world stage for any performer.

It struck me the world is having its Latin America moment (or perhaps several of them), which led me to reflect on the connections between the singer from Puerto Rico and the Pope from Chicago.

On the surface of it, one could argue that these two are worlds apart. But not so, and to truly understand the link between them, one has to look past both LA’s Crypto.com arena and Rome’s Vatican.

The Purpose

While one sings about late-night escapades and the other delivers encyclicals on the dignity of labor, they are both grappling with the same crisis: how to find a “sacred” center in a world that feels increasingly hollow.

The Roots

Both Bad Bunny and Pope Leo XIV are products of the middle class, raised in households where work was a necessity and faith was the underlying foundation of daily life.

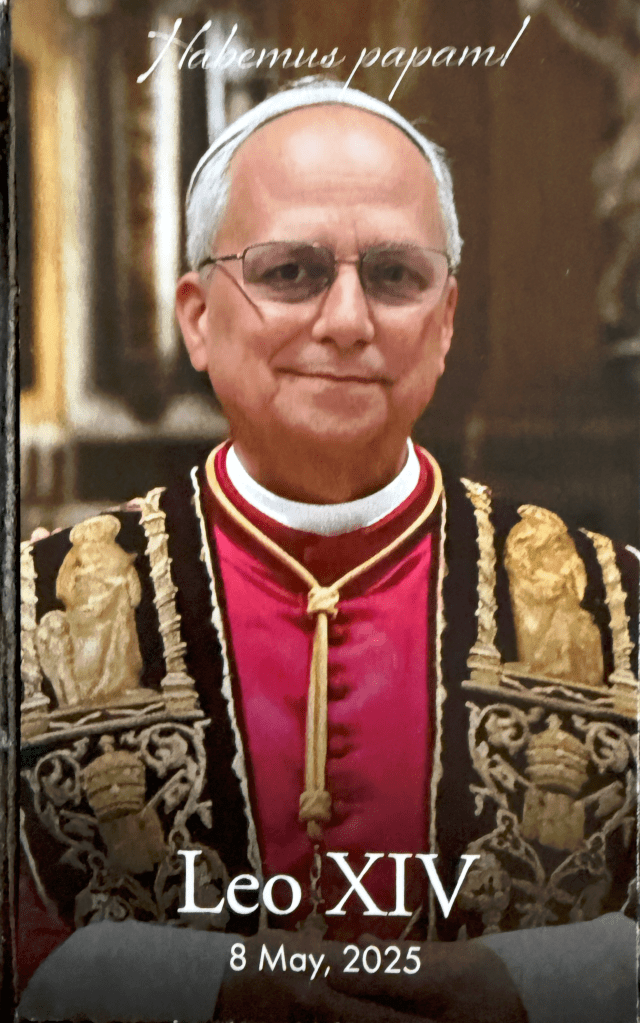

Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio grew up in a rural barrio of Puerto Rico, the son of a truck driver and a schoolteacher. Similarly, Robert Francis Prevost—the man who would become Pope Leo XIV—was raised in the working-class South Side of Chicago by a school principal and a librarian.

These were not lives of luxury, but of keeping the family ship afloat — lives focused on the light bill, the local news and the steady rhythm of the parish.

This shared foundation in the local Catholic church is their most striking biographical link. Both were altar boys and choir singers, a formative experience that teaches a young person how to navigate sacred space and command the attention of a congregation.

While Benito eventually traded the choir loft for the recording studio, he carried that liturgical training with him. He treats his concerts as modern-day masses, complete with communal rituals and a preoccupation with “La Nueva Religión.”

Leo XIV, meanwhile, took that same discipline into the missions of Peru, where he spent decades living in the periphery. For both men, the Church was not just a building, but a training ground for understanding human dignity and the power of a shared voice.

The Outsiders

Beyond their upbringings, they share a distinct “outsider-insider” energy. Bad Bunny conquered the music industry without ever assimilating into the English-speaking mainstream, forcing the world to listen on his terms.

Leo XIV, as the first American Pope, broke a centuries-old European glass ceiling while remaining a “dark horse” who many believed could never be elected.

Both are bridge-builders who represent the triumph of the Global South—Leo through his naturalized Peruvian citizenship and missionary heart, and Benito through his refusal to abandon the slang and struggles of Puerto Rico.

In 2026, they stand as the twin pillars of a new American era: one speaking from the balcony of St. Peter’s and the other from the stage of the Grammys, both reminding us that the center of the world has shifted.

Lyrics as Liturgy: The “Nueva Religión”

While Bad Bunny’s music is often dismissed as hedonistic, a closer look at his discography reveals a preoccupation with the “common good” that mirrors Catholic Social Teaching (CST).

- The Principle of Solidarity: In his 2023-2025 tracks, Benito often shifts from “I” to “We.” In songs like “El Apagón,” he critiques the privatization of Puerto Rico’s power grid. This isn’t just a party anthem; it’s a protest against the exploitation of the poor—a direct echo of Leo XIV’s namesake, Leo XIII, who in Rerum Novarum argued that the state must protect the worker from the “greed of speculators.”

- The Dignity of the Person: Bad Bunny’s vocal defense of the LGBTQ+ community and women (seen in “Andrea” or “Solo de Mí”) is his version of “human dignity.” While the Church’s definitions differ, Leo XIV’s focus on “integral human development” and his historic calls for the protection of marginalized groups in Peru show a shared priority: the belief that no human being is disposable.

The “Latin American Yankee”: A Bridge of Identity

Pope Leo XIV (Robert Francis Prevost) is a walking contradiction: a Chicago-born Augustinian who is also a naturalized Peruvian citizen. This dual identity underlies his papacy, and it’s the exact same energy Bad Bunny brings to the global stage.

- The Language of the Heart: Leo XIV shocked the world by delivering his first Urbi et Orbi with a heavy emphasis on Spanish, specifically acknowledging his “beloved Diocese of Chiclayo.”

- Refusing to Assimilate: Just as Bad Bunny refuses to record a “crossover” album in English to please American markets, Leo XIV refuses to let the Papacy be viewed through a purely Eurocentric or “American Superpower” lens. He is the first Pope to understand the North but chooses to speak for the South.

The Challenge of the “New Industrial Revolution”

One of the most striking connections between the pair is their shared wariness of artificial intelligence (AI) and digital isolation. While Bad Bunny critiques the “fake” life of instagram, Leo warns against “algorithmic logic” that replaces human empathy and calls for a “Global Treaty on AI Ethics” in his first January message of 2026.

Bad Bunny preaches “Estamos Bien”—a radical focus on being present in the moment. The Pope focuses on the “Theology of Encounter”—physically being with the poor rather than viewing them through a screen.

Last weekend’s Grammys and this weekend’s Super Bowl can be viewed as the “liturgies” of our secular age. When Bad Bunny takes the stage, he isn’t just performing; he is enacting a ritual for a generation that might ignore the pews but still craves communal transcendence.

Pope Leo XIV seems to recognize this. Unlike previous pontiffs who might have condemned the “profanity” of reggaeton, Leo’s background as a missionary in the Peruvian trenches gives him a different perspective. He understands that for the youth in the barrios of Lima or the suburbs of Chicago, Benito’s “Nueva Religion” is often the only place they feel seen.

So, one uses a microphone, the other a miter. One celebrates the flesh, the other the spirit. But both are reminding us that the Americas—from the streets of San Juan to the missions of Peru—represent the moral and cultural heart of the world.

So, on Sunday, I’ll be glued to the television for two reasons, watching both the game and the halftime show. I’d say neither one is to be missed.

Leave a comment